•Leukemia, also spelled leukemias, is a group of blood cancers that usually begin in the bone marrow and result in high numbers of abnormal blood cells. These blood cells are not fully developed and are called blasts or leukemia cells.

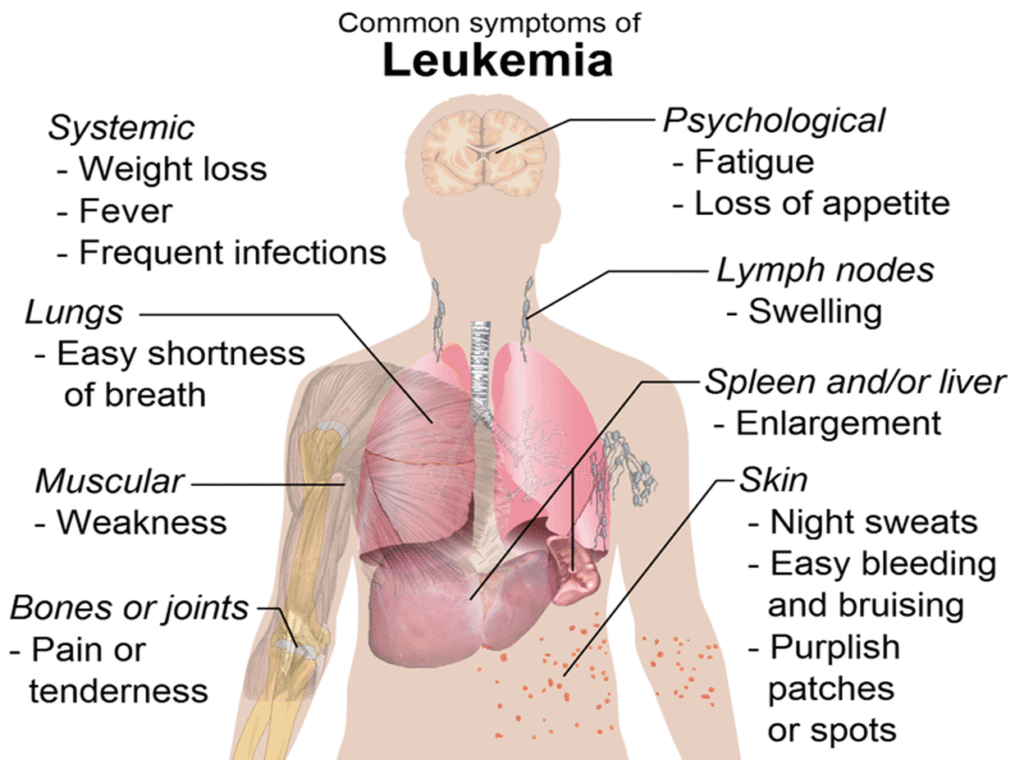

•Symptoms may include bleeding and bruising problems, feeling tired, fever, and an increased risk of infections. These symptoms occur due to a lack of normal blood cells. Diagnosis is typically made by blood tests or bone marrow biopsy.

•The leukemias are a group of disorders characterized by the accumulation of malignant white cells in the bone marrow and blood. These abnormal cells cause symptoms because of:

•(i) bone marrow failure (e.g. anaemia, neutropenia, thrombocytopenia); and

•(ii) infiltration of organs (e.g. liver, spleen, lymph nodes, meninges, brain, skin or testes).

Classification of leukemia

•The main classification is into four types: acute and chronic leukemias, which are further subdivided into lymphoid or myeloid.

•Acute leukemias are usually aggressive diseases in which malignant transformation occurs in the haemopoietic stem cell or early progenitors.

•Genetic damage is believed to involve several key biochemical steps resulting in

•(i) an increased rate of proliferation,

•(ii) reduced apoptosis and

•(iii) a block in cellular differentiation.

•Together these events cause accumulation in the bone marrow of early haemopoietic cells known as blast cells.

•The dominant clinical feature of acute leukemia is usually bone marrow failure caused by accumulation of blast cells, although organ infiltration also occurs.

•If untreated, acute leukemias are usually rapidly fatal, although with modern treatments most younger patients are ultimately cured of their disease.

•Acute leukemia is characterized by a rapid increase in the number of immature blood cells. The crowding that results from such cells makes the bone marrow unable to produce healthy blood cells. Immediate treatment is required in acute leukemia because of the rapid progression and accumulation of the malignant cells, which then spill over into the bloodstream and spread to other organs of the body. Acute forms of leukemia are the most common forms of leukemia in children.

•Chronic leukemia is characterized by the excessive buildup of relatively mature, but still abnormal, white blood cells. Typically taking months or years to progress, the cells are produced at a much higher rate than normal, resulting in many abnormal white blood cells. Whereas acute leukemia must be treated immediately, chronic forms are sometimes monitored for some time before treatment to ensure maximum effectiveness of therapy. Chronic leukemia mostly occurs in older people but can occur in any age group.

•Additionally, the diseases are subdivided according to which kind of blood cell is affected. This divides leukemias into lymphoblastic or lymphocytic leukemias and myeloid or myelogenous leukemias:

•In lymphoblastic or lymphocytic leukemias, the cancerous change takes place in a type of marrow cell that normally goes on to form lymphocytes, which are infection-fighting immune system cells. Most lymphocytic leukemias involve a specific subtype of lymphocyte, the B cell.

•In myeloid or myelogenous leukemias, the cancerous change takes place in a type of marrow cell that normally goes on to form red blood cells, some other types of white cells, and platelets.

Specific types

•Acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) is the most common type of leukemia in young children. It also affects adults, especially those 65 and older. Standard treatments involve chemotherapy and radiotherapy. The survival rates vary by age: 85% in children and 50% in adults.

•Subtypes include precursor B acute lymphoblastic leukemia, precursor T acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Burkitt’s leukemia, and acute biphenotypic leukemia.

•Chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) most often affects adults over the age of 55. It sometimes occurs in younger adults, but it almost never affects children. Two-thirds of affected people are men. The five-year survival rate is 75%. It is incurable, but there are many effective treatments. One subtype is B-cell prolymphocytic leukemia, a more aggressive disease.

•Acute myelogenous leukemia (AML) occurs more commonly in adults than in children, and more commonly in men than women. It is treated with chemotherapy. The five-year survival rate is 40%, except for APL (Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia), which has a survival rate greater than 90%. Subtypes of AML include acute promyelocytic leukemia, acute myeloblastic leukemia, and acute megakaryoblast leukemia.

•Chronic myelogenous leukemia (CML) occurs mainly in adults; a very small number of children also develop this disease. It is treated with imatinib (Gleevec in United States, Gleevec in Europe) or other drugs. The five-year survival rate is 90%. One subtype is chronic myelomonocytic leukemia.

•Pre-leukemia.

•Transient myeloproliferative disease, also termed transient leukemia, involves the abnormal proliferation of a clone of non-cancerous megakaryoblasts.

•The disease is restricted to individuals with Down syndrome or genetic changes similar to those in Down syndrome, develops in a baby during pregnancy or shortly after birth, and resolves within 3 months or, in ~10% of cases, progresses to acute megakaryoblast leukemia. Transient myeloid leukemia is a pre-leukemic condition.

Signs and symptoms:

•The most common symptoms in children are easy bruising, pale skin, fever, and an enlarged spleen or liver.

•Damage to the bone marrow, by way of displacing the normal bone marrow cells with higher numbers of immature white blood cells, results in a lack of blood platelets, which are important in the blood clotting process.

•This means people with leukemia may easily become bruised, bleed excessively, or develop pinprick bleeds (petechiae).

•White blood cells, which are involved in fighting pathogens, may be suppressed or dysfunctional.

•This could cause the person’s immune system to be unable to fight off a simple infection or to start attacking other body cells.

•Because leukemia prevents the immune system from working normally, some people experience frequent infection, ranging from infected tonsils, sores in the mouth, or diarrhea to life-threatening pneumonia or opportunistic infections.

•Finally, the red blood cell deficiency leads to anemia, which may cause dyspnea and pallor.

•Some people experience other symptoms, such as feeling sick, having fevers, chills, night sweats, feeling fatigued and other flu-like symptoms. Some people experience nausea or a feeling of fullness due to an enlarged liver and spleen; this can result in unintentional weight loss.

•Blasts affected by the disease may come together and become swollen in the liver or in the lymph nodes causing pain and leading to nausea.

•If the leukemic cells invade the central nervous system, then neurological symptoms (notably headaches) can occur. Uncommon neurological symptoms like migraines, seizures, or coma can occur as a result of brain stem pressure.

•All symptoms associated with leukemia can be attributed to other diseases. Consequently, leukemia is always diagnosed through medical tests.

The etiology of haemopoietic malignancy

•Cancer results from the accumulation of genetic mutations within a cell and the number present varies widely from over 100 in some cancers to about 10 in most hematological malignancies (Fig. 11.3).

•Factors such as genetic inheritance and environmental lifestyle will influence the risk of developing a malignancy, but most cases of leukemia and lymphoma appear to result simply as a result of the chance acquisition of critical genetic changes.

•Inherited factors

•The incidence of leukemia is greatly increased in some genetic diseases such as Down’s syndrome where acute leukemia occurs with a 20‐ to 30‐fold increased frequency. Additional disorders are Bloom’s syndrome, Fanconi’s anemia, ataxia telangiectasia, neurofibromatosis, Klinefelter’s syndrome and Weskit–Aldrich syndrome.

•There is also a weak familial tendency in diseases such as acute myeloid leukemia (AML), CLL, Hodgkin lymphoma and non‐Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL), although the genes predisposing to this increased risk are largely unknown.

Environmental influences

•Chemicals

•Chronic exposure to industrial solvents or chemicals such as benzene is a known but rare cause of myelodysplasia or AML.

•Drugs

•Alkylating agents, such as chlorambucil or melphalan, predispose to later development of AML, especially if combined with radiotherapy. Etoposide is associated with a risk of the development of secondary leukemia associated with balanced translocations including that of the MLL gene at 11q23.

•Radiation

•Radiation, especially to the marrow, is leukemogenic. This is illustrated by an increased incidence of leukemia in survivors of the atom bomb explosions in Japan.

•Infection

•Infections are responsible for around 18% of all cancers and contribute to a range of haematological malignancies.

•Viruses

•Viral infection is associated with several types of haemopoietic malignancy, especially different subtypes of lymphoma (see Table 20.2). The retrovirus human T‐lymphotropic virus type 1 is the cause of adult T‐cell leukemia/lymph, although most people infected with this virus do not develop the tumor. Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is associated with almost all cases of endemic (African) Burkitt lymphoma, post‐transplant lymphoproliferative disease (see p. 261) and a proportion of patients with Hodgkin lymphoma. Human herpes virus 8 infection (Kaposi’s sarcoma‐associated virus) causes Kaposi’s sarcoma and primary effusion lymphoma.

•HIV infection is associated with an increased incidence of lymphomas at unusual sites such as the central nervous system. These HIV‐associated lymphomas are usually of B‐cell origin and of high‐grade histology.

•Bacteria

•Helicobacter pylori infection has been implicated in the pathogenesis of gastric mucosa B‐cell (MALT) lymphoma (see p. 221) and antibiotic treatment may even bring about disease remission.

•Protozoa

•Endemic Burkitt lymphoma occurs in the tropics, particularly in malarial areas. It is thought that malaria may alter host immunity and predispose to tumor formation as a result of EBV infection.

The genetics of haemopoietic malignancy

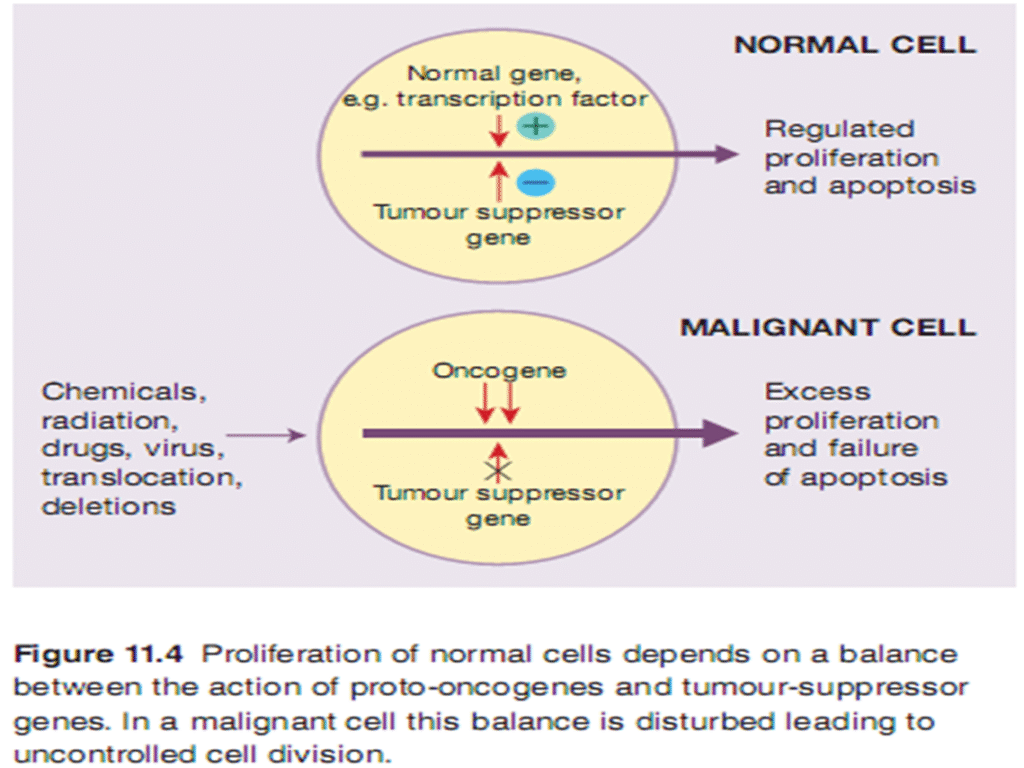

•Malignant transformation occurs as a result of the accumulation of genetic mutations in cellular genes. The genes that are involved in the development of cancer can be divided broadly into two groups: oncogenes and tumor‐suppressor genes.

•Oncogenes

•Oncogenes arise because of gain‐of‐function mutations or inappropriate expression pattern in normal cellular genes called proto‐oncogenes (Fig. 11.4). Oncogenic versions are generated when the activity of proto‐oncogenes is increased, or they acquire a novel function.

•This can occur in a number of ways including translocation, mutation or duplication. In general, these mutations affect the processes of cell signaling, cell differentiation and survival.

•One of the striking features of hematological malignancies, in contrast to most solid tumors, is their high frequency of chromosomal translocations. Several oncogenes are involved in suppression of apoptosis, of which the best example is BCL‐2 which is overexpressed in follicular lymphoma.

•The types of mutations that are detected in a case of cancer fall into two broad groups.

•Driver mutations are those that confer a selective growth advantage to a cancer cell. Recent data suggest that the combinatorial sequence in which different driver mutations occur in a tumor may affect the clinical features of the resulting disease.

•Passenger mutations do not confer a growth advantage and may have already been present in the cell from which the cancer arose or arise as a neutral genetic change in the proliferating cell. It is therefore important that targeted drug treatments are directed against the activity of driver mutations.

•Tyrosine kinases

•These are enzymes which phosphorylate proteins on tyrosine residues, and they are important mediators of intracellular signaling. Mutations of tyrosine kinases underlie a large number of hematological malignancies, and they are the targets of many extremely effective new drugs.

•Common examples discussed in the relevant chapters include ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), JAK2 in myeloproliferative neoplasms, FLT3 in AML, KIT in both systemic mastocytosis and AML, and Bruton kinase in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and other lymphoproliferative disorders.

•Tumor‐suppressor genes

•Tumor‐suppressor genes may acquire loss‐of‐function mutations, usually by point mutation or deletion, which lead to malignant transformation (Fig. 11.4). Tumor‐suppressor genes commonly act as components of control mechanisms that regulate entry of the cell from the G1 phase of the cell cycle into the S phase or passage through the S phase to G2 and mitosis (see Fig. 1.7).

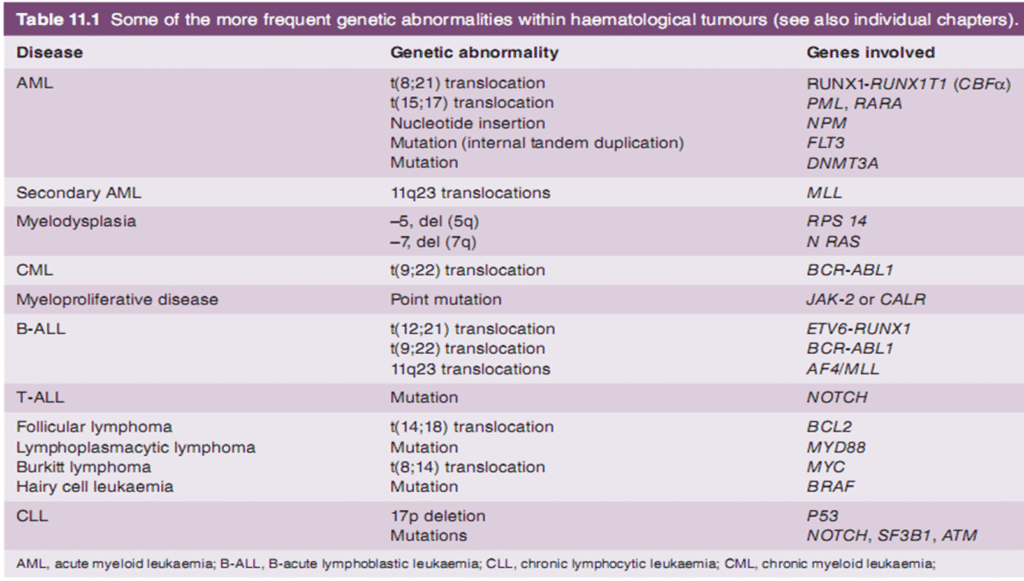

•Examples of oncogenes and tumor‐ suppressor genes involved in haemopoietic malignancies are shown in Table 11.1. The most significant tumor‐suppressor gene in human cancer is p53 which is mutated or inactivated in over 50% of cases of malignant disease, including many haemopoietic tumors.

•Clonal progression

•Malignant cells appear to arise as a multistep process with acquisition of mutations in different intracellular pathways.

•This may occur by a linear evolution, in which the final clone harbors all the mutations that arose during evolution of the malignancy (Fig. 11.5a), or by branching evolution, in which there is more than one clone of cells characterized by different somatic mutations but which share at least one mutation trace-able back to a single ancestral cell (Figure 11.5b).

•During this progression of the disease, one sub clone may gradually acquire a growth advantage. Selection of sub clones may also occur during treatment which may selectively kill some sub clones but allow others to survive and new clones to appear (Fig. 11.6).

Progression of subclinical clonal hematological abnormalities to clinical disease

•The use of sensitive immunological and molecular tests has shown many healthy individuals harbor clones of cells which have acquired somatic mutations and from which overt hematological clinical disease may arise (Table 11.2).

•This is particularly frequent in the elderly. Examples include clones of cells identical to those of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which can be present in the blood of individuals with a normal lymphocyte count, and the finding of clones of cells harboring mutations, such as of TET2, which are characteristic of myeloid malignancy and yet may be present in a normal appearing bone marrow in nearly a fifth of elderly healthy subjects.

•Progression of benign monoclonal paraproteinemia to myeloma has been well recognized for many decades.

Specific examples of genetic abnormalities in hematological malignancies

•The genetic abnormalities underlying the different types of leukemia and lymphoma are described with the diseases which are themselves increasingly classified according to genetic change rather than morphology.

•The types of gene abnormality include the following

Point mutation

•This is illustrated by the Val617Phe mutation in the JAK2 gene, which leads to constitutive activation of the JAK2 protein in most cases of myeloproliferative disease (see Chapter 15).

•Mutations within the RAS oncogenes or p53 tumor‐suppressor gene are common in many haemopoietic malignancies.

•The point mutation may involve several base pairs. In 35% of cases of AML the nucleo-phosmin gene shows an insertion of four base pairs, resulting in a frame shift change.

•Internal tandem duplication or point mutations occur in the FLT3 gene in 30% of cases of AML.

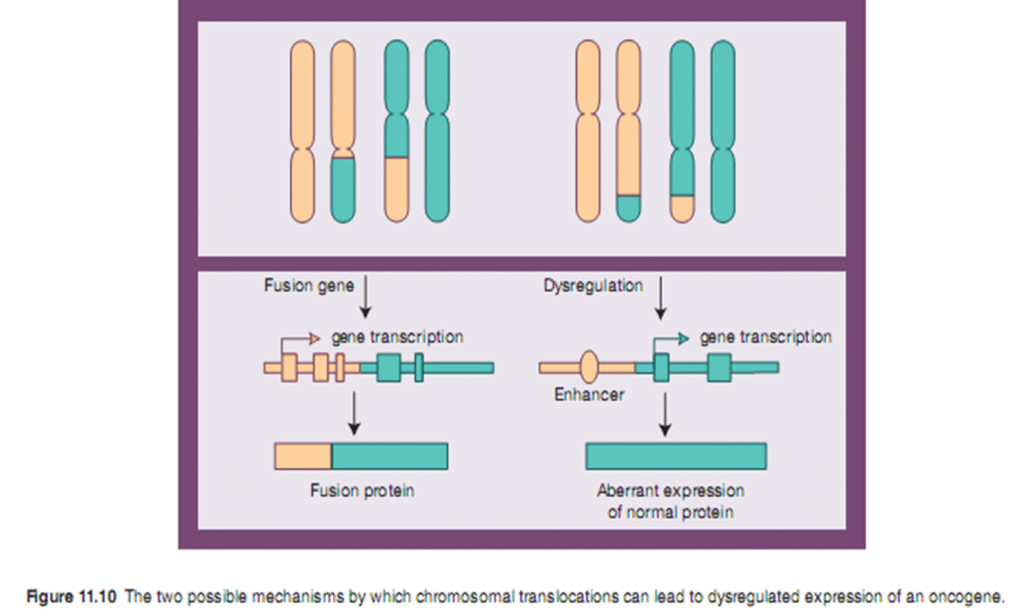

Translocations

•These are a characteristic feature of hematological malignancies and there are two main mechanisms whereby they may contribute to malignant change (Fig. 11.10).

•1 Fusion of parts of two genes to generate a chimeric fusion gene that is dysfunctional or encodes a novel ‘fusion protein’, e.g. BCR‐ABL1 in t(9;22) in CML (see Fig. 14.1), RARα‐PML in t(15;17) in acute promyelocytic leukemia or ETV6‐RUNX1in t(12; 21) in B‐ALL.

• 2 Overexpression of a normal cellular gene, e.g. overexpression of BCL‐2 in the t (14;18) translocation of follicular lymphoma or of MYC in Burkitt lymphoma.

•Interestingly, this class of translocation nearly always involves a TCR or immunoglobulin gene locus, presumably as a result of aberrant activity of the recombinase enzyme which is involved in immunoglobulin or TCR gene rearrangement in immature B or T cells.

•Deletions

•Chromosomal deletions may involve a small part of a chromosome, the short or long arm (e.g. 5q–) or the entire chromosome (e.g. monosomy 7).

•The critical event is probably loss of a tumor‐suppressor gene or of a microRNA as in the 13q14 deletion in CLL (see below). Loss of multiple chromosomes is termed hypodiploidy and is seen frequently in ALL.

•Duplication or amplification

•In chromosomal duplication (e.g. trisomy 12 in CLL) or gene amplification, gains are common in chromosomes 8, 12, 19, 21 and Y.

•Gene amplification is increasingly recognized within haemopoietic malignancy, and an example is that involving the MLL gene

Epigenetic Alterations

•Gene expression in cancer may be dysregulated not only by structural changes to the genes themselves but also by alterations in the mechanism by which genes are transcribed.

•These changes are called epigenetic and are stably inherited with each cell division, so they are passed on as the malignant cell divides.

•The most important mechanisms are:

• 1 Methylation of cytosine residues in DNA.

•2 Enzymatic alterations, such as acetylation or methylation, of the histone proteins that package DNA within the cell; and

• 3 Alterations in enzymes that mediate the splicing machinery (see Fig. 16.1).

•They are particularly important in the myeloid malignancies. Demethylating agents, such as azacytidine, increase gene transcription and are valuable in treating myelodysplasia (MDS) and AML.

•MicroRNAs

•Chromosomal abnormalities, both deletions and amplifications, can result in loss or gain of short (micro) RNA sequences.

•These are normally transcribed but not translated. MicroRNAs control expression of adjacent or distally located genes. Deletion of the miR15a/miR16‐1 locus may be relevant to CLL development with the common 13q14 deletion, and deletions of other microRNAs have been described in AML and other hematological malignancies.