•Hypochromic anemia, or Hypochromic anaemia, is a generic term for any type of anemia in which the red blood cells (erythrocytes) are paler than normal. (Hypo– refers to less, and chromic means color.)

•A normal red blood cell will have an area of pallor in the center of it; it is biconcave disk shaped. In hypochromic cells, this area of central pallor is increased.

•This decrease in redness is due to a disproportionate reduction of red cell hemoglobin (the pigment that imparts the red color) in proportion to the volume of the cell.

•Clinically the color can be evaluated by the Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin (MCH) or Mean Corpuscular Hemoglobin Concentration (MCHC).

•The MCHC is considered the better parameter of the two as it adjusts for effect the size of the cell has on its color.

•Hypochromia is clinically defined as below the normal MCH reference range of 27-33 picograms/cell in adults or below the normal MCHC reference range of 33-36 g/dL in adults.

•Red blood cells will also be small (microcytic), leading to substantial overlap with the category of microcytic anemia.

•The most common causes of this kind of anemia are iron deficiency and thalassemia.

•Hypochromic anemia was historically known as chlorosis or green sickness for the distinct skin tinge sometimes present in patients, in addition to more general symptoms such as a lack of energy, shortness of breath, dyspepsia, headaches, a capricious or scanty appetite and amenorrhea.

Nutritional and Metabolic Aspects of Iron

•Body iron distribution and transport

•The transport and storage of iron is largely mediated by three proteins:

•transferrin,

•transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1)

•ferritin.

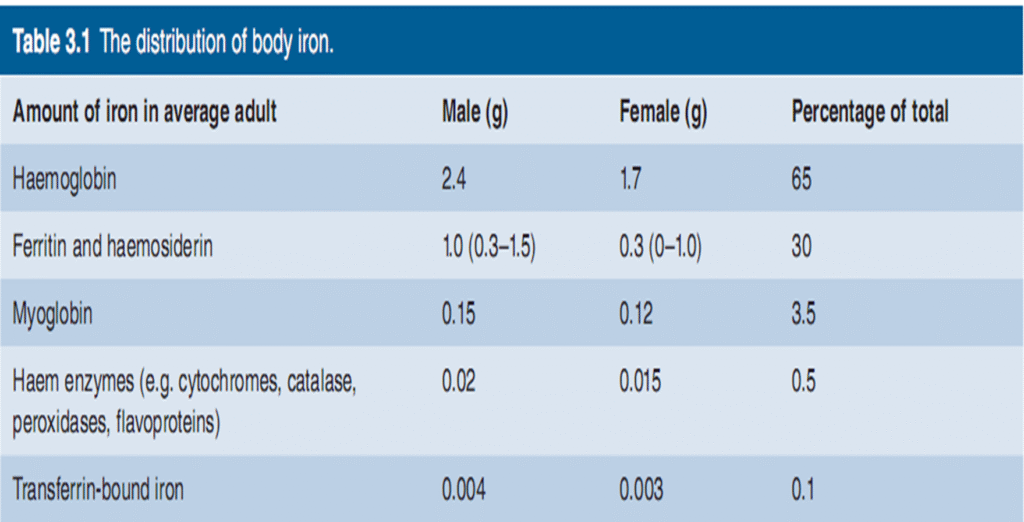

•Transferrin molecules can each contain up to two atoms of iron. Transferrin delivers iron to tissues that have transferrin receptors, especially erythroblasts in the bone marrow which incorporate the iron into hemoglobin (Figs 2.7, 3.2).

•The transferrin is then reutilized, at the end of their life, red cells are broken down in the macrophages of the reticule-endothelial system, and the iron is released from hemoglobin, enters the plasma and provides most of the iron on transferrin.

•Only a small proportion of plasma transferrin iron comes from dietary iron, absorbed through the duodenum and jejunum.

•Some iron is stored in the macrophages as ferritin and haemosiderin, the amount varying widely according to overall body iron status.

•Ferritin is a water‐soluble protein–iron complex. It is made up of an outer protein shell, apoferritin, consisting of 22 subunits and an iron–phosphate–hydroxide core.

•It contains up to 20% of its weight as iron and is not visible by light microscopy.

•Hemosiderin is an insoluble protein–iron complex of varying composition containing approximately 37% iron by weight.

•It is derived from partial lysosomal digestion of ferritin molecules and is visible in macrophages and other cells by light microscopy after staining by Perls’ (Prussian blue) reaction (see Fig. 3.10).

•Iron in ferritin and haemosiderin is in the ferric form. It is mobilized after reduction to the ferrous form.

•A copper‐containing enzyme, caeruloplasmin, catalyze oxidation of the iron to the ferric form for binding to plasma transferrin.

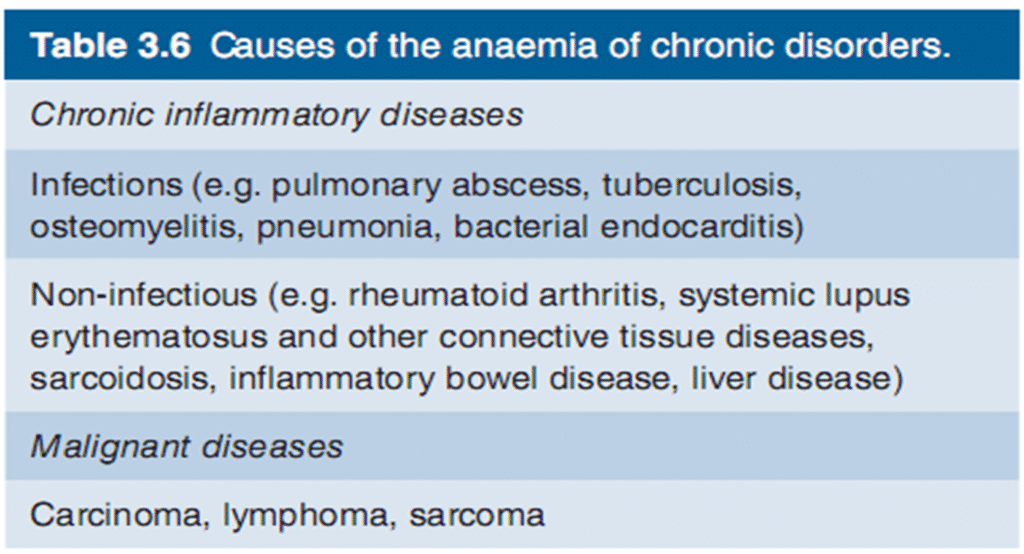

•Iron is also present in muscle as myoglobin and in most cells of the body in iron‐containing enzymes (e.g. cytochromes or catalase) (Table 3.1).

•This tissue iron is less likely to become depleted than hemosiderin, ferritin and hemoglobin in states of iron deficiency, but some reduction of these haem‐containing enzymes may occur.

Figure 3.2 Daily iron cycle. Most of the iron in the body is contained in circulating hemoglobin (see Table 3.1) and is reutilized for hemoglobin synthesis after the red cells die. Iron is transferred from macrophages to plasma transferrin and so to bone marrow erythroblasts. Iron absorption is normally just sufficient to make up for iron loss. The dashed line indicates ineffective erythropoiesis.

Regulation of Ferritin and Transferrin Receptor 1 Synthesis

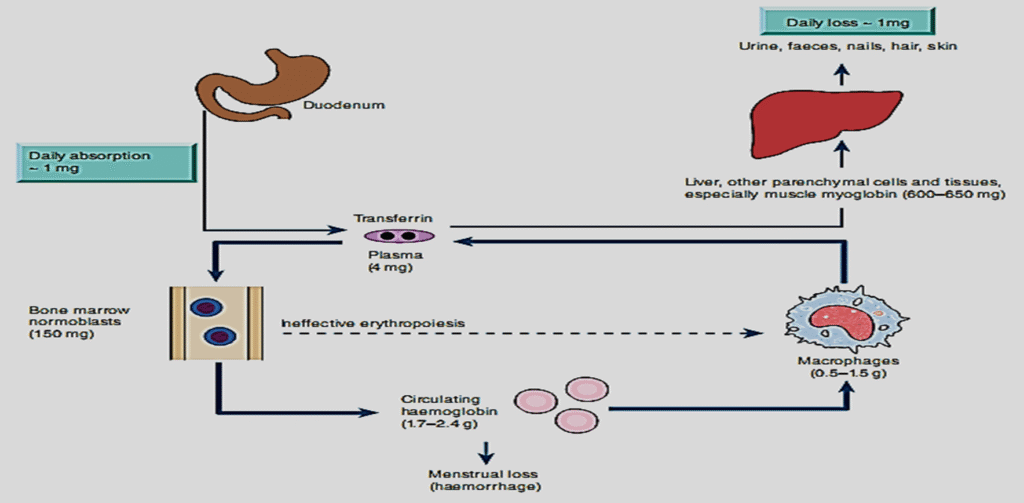

•The levels of ferritin, TfR1, δ‐aminolaevulinic acid synthase (ALA‐S) and divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT‐1) are linked to iron status so that iron overload causes a rise in tissue ferritin and a fall in TfR1 and DMT‐1, whereas in iron deficiency ferritin and ALA‐S are low and TfR1 increased.

•Tis linkage arises through the binding of an iron regulatory protein (IRP) to iron response elements (IREs) on the ferritin, TfR1, ALA‐S and DMT‐1 mRNA molecules.

•Iron deficiency increases the ability of IRP to bind to the IREs whereas iron overload reduces the binding.

•The site of IRP binding to IREs, whether upstream (5′) or downstream (3′) from the coding gene, determines whether the amount of mRNA and so protein produced is increased or decreased (Fig. 3.3).

•Upstream binding reduces translation, whereas downstream binding stabilizes the mRNA, increasing translation and so protein synthesis.

•When plasma iron is raised and transferrin is saturated, the amount of iron transferred to parenchymal cells (e.g. those of the liver, endocrine organs and heart) is increased and this is the basis of the pathological changes associated with iron loading conditions.

•There may also be free iron in plasma which is toxic to different organs.

•Figure 3.3 Regulation of transferrin receptor 1 (TfR1), divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT‐1) and ferritin expression by iron regulatory protein (IRP) sensing of intracellular iron levels.

•IRPs are able to bind to stem‐loop structures called iron response elements (IREs).

•IRP binding to the IRE within the 3′ untranslated region of TfR1 and DMT‐1 leads to stabilization of the mRNA and increased protein synthesis, whereas IRP binding to the IRE within the 5′ untranslated region of ferritin and δ‐aminolaevulinic acid synthase (ALA‐S) mRNA reduces translation.

•IRPs can exist in two states: at times of high iron levels the IRP binds iron and exhibits a reduced affinity for the IREs, whereas when iron levels are low the binding of IRPs to IREs is increased.

•In this way synthesis of TfR , ALA‐S, DMT‐1 and ferritin is coordinated to physiological requirements.

Hepcidin

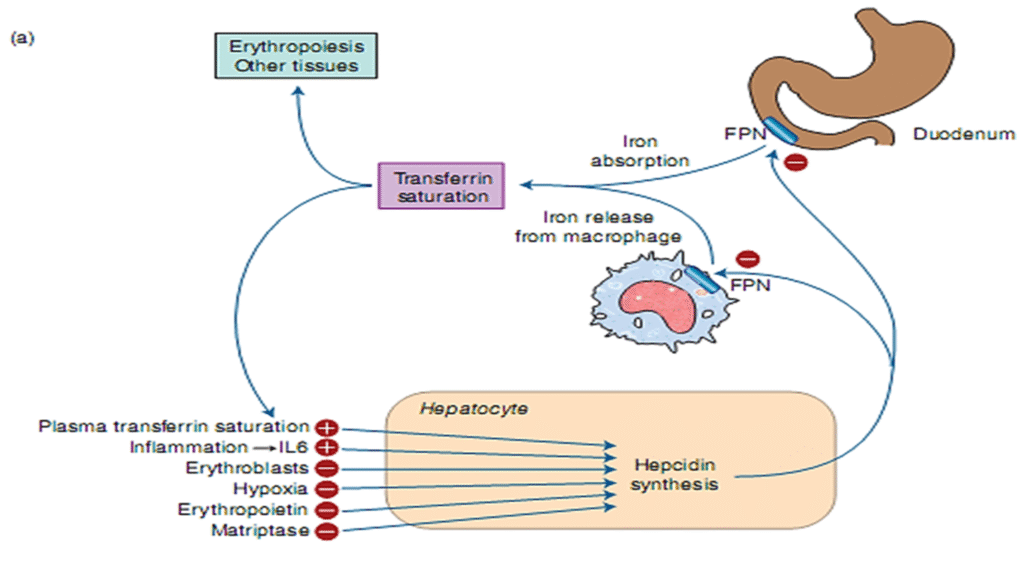

•Hepcidin is a polypeptide produced by liver cells. It is the major hormonal regulator of iron homeostasis (Fig. 3.4a).

•It inhibits iron release from macrophages and from intestinal epithelial cells by its interaction with the transmembrane iron exporter, ferroprotein.

•It accelerates degradation of ferroprotein mRNA.

•Raised hepcidin levels therefore profoundly affect iron metabolism by reducing its absorption and release from macrophages.

Figure 3.4 (a) Hepcidin reduces iron absorption and release from macrophages by stimulating degradation of ferroprotein. Its synthesis is increased by transferrin saturation and inflammation but reduced by increased erythropoiesis, erythropoietin, hypoxia and matriptase.

Control of Hepcidin Expression

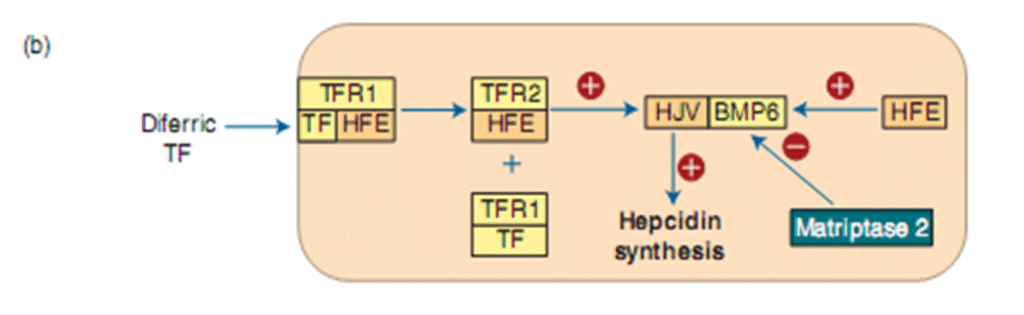

•Membrane‐bound hemojuvelin (HJV) is a co‐receptor with bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) which stimulates hepcidin expression (Fig. 3.4b).

•A complex between HFE and transferrin receptor 2 (TfR2) promotes HJV binding to BMP.

•The amount of HFE–TfR2 complex is determined by the degree of iron saturation of transferrin as follows.

•Di ferric transferrin competes with TfR1 for binding to HFE. The more Di ferric transferrin, the less TfR1 is bound to HFE and more HFE is available to bind to TfR2, with consequently increased hepcidin synthesis.

•Low concentrations of Di ferric transferrin, as in iron deficiency, allow HFE binding to TfR1, reducing the amount of HFE able to bind TfR2 and thus reducing hepcidin secretion.

•HFE also increases BMP expression, directly increasing hepcidin synthesis.

•Matriptase 2 digests membrane‐bound HJV. In iron deficiency, increased matriptase activity therefore results in decreased hepcidin synthesis.

•Erythroblasts secrete two proteins, erythroferrone and GDF 15, which suppress hepcidin secretion.

•In conditions with increased numbers of early erythroblasts in the marrow (e.g. conditions of ineffective erythropoiesis, such as thalassemia major), iron absorption is increased because of suppression of hepcidin secretion by these proteins.

•Hypoxia also suppresses hepcidin synthesis, whereas in inflammation interleukin 6 (IL‐6) and other cytokines increase hepcidin synthesis (Fig. 3.4a).

•(b) The proposed mechanism by which the degree of transferrin saturation by iron affects hepcidin synthesis. BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; HJV, hemojuvelin; TFR1 and 2, transferrin receptor 1 and 2.

•BMP stimulates hepcidin synthesis and this is enhanced by HJV binding to BMP. Di ferric transferrin competes with TFR1 for binding of HFE.

•The more Di ferric transferrin, the less TRF1 is bound to HFE and more HFE is available to bind to TFR2. The HFE/TFR2 complex promotes HJV binding to BMP and so promotes hepcidin synthesis.

•Low concentrations of Di ferric transferrin, as in iron deficiency, allow HFE binding to TFR1, reducing the amount of HFE able to bind TFR2 and thus reducing HJV binding to BMP and so reducing hepcidin secretion. HFE also enhances BMP expression directly, but mutated HFE inhibits its expression.

Dietary Iron

•Iron is present in food as ferric hydroxides, ferric–protein and haem–protein complexes.

•Both the iron content and the proportion of iron absorbed differ from food to food; in general meat, in particular liver, is a better source than vegetables, eggs or dairy foods.

•The average Western diet contains 10–15 mg iron daily from which only 5–10% is normally absorbed.

•The proportion can be increased to 20–30% in iron deficiency or pregnancy (Table 3.2) but even in these situations most dietary iron remains unabsorbed.

Iron Absorption

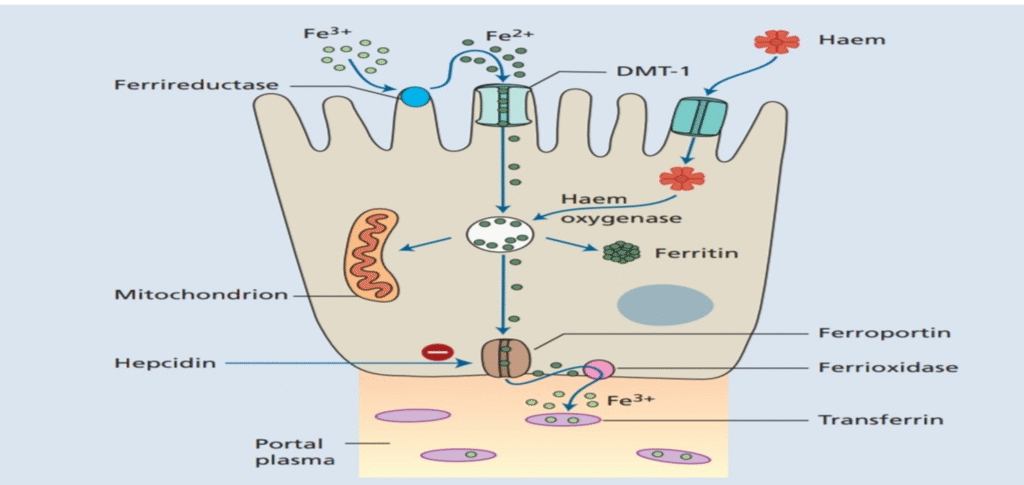

•Organic dietary iron is partly absorbed as haem and partly broken down in the gut to inorganic iron.

•Absorption occurs through the duodenum.

•Haem is absorbed through a receptor, yet to be identified, on the apical membrane of the duodenal enterocyte. Haem is then digested to release iron.

•Inorganic iron absorption is favored by factors such as acid and reducing agents that keep iron in the gut lumen in the Fe 2+ rather than the Fe3+ state (Table 3.2).

•The protein DMT – 1 is involved in transfer of iron from the lumen of the gut across the enterocyte microvilli (Fig. 3.5 ).

•Ferroprotein at the basolateral surface controls exit of iron from the cell into portal plasma.

•The amount of iron absorbed is regulated according to the body ’ s needs by changing the levels of DMT – 1 and ferroportin.

•For DMT – 1 this occurs by the same mechanism (IRP/IRE binding) by which transferrin receptor is increased in iron deficiency (Fig. 3.3).

•Hepcidin is a major regulator by affecting ferroprotein concentration. Low hepcidin levels in iron deficiency allow increased ferroprotein levels and so more iron to enter portal plasma.

•Ferrireductase present at the apical surface converts iron from the Fe 3+ to Fe 2+ state and another enzyme, Hephaestion (ferroxidase) (which contains copper), converts Fe 2+ to Fe 3+ at the basal surface prior to binding to transferrin.

Figure 3.5 The regulation of iron absorption. Dietary ferric (Fe 3+) iron is reduced to Fe 2+ and its entry to the enterocyte is through the divalent cation binder DMT- 1. Its export into portal plasma is controlled by ferroportin. It is oxidized before binding to transferrin in plasma. Haem is absorbed after binding to its receptor protein.

Iron Requirements

•The amount of iron required each day to compensate for losses from the body and for growth varies with age and sex; it is highest in pregnancy, adolescent and menstruating females.

•Therefore, these groups are particularly likely to develop iron deficiency if there is additional iron loss or prolonged reduced intake.

Iron deficiency

•Clinical features:

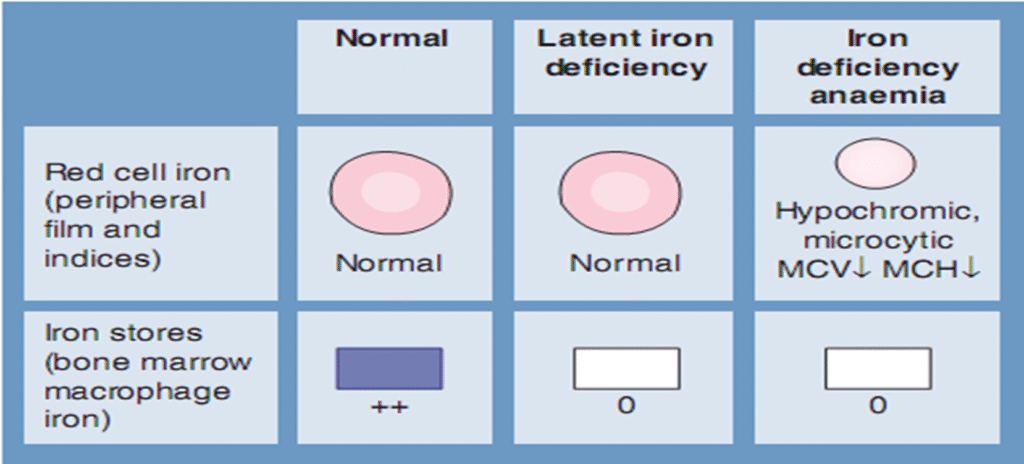

•When iron deficiency is developing, the reticuloendothelial stores (hemosiderin and ferritin) become completely depleted before anemia occurs (Fig. 3.6).

•As the condition develops the patient may show the general symptoms and signs of anemia and also a painless glossitis, angular stomatitis, brittle, ridged or spoon nails (koilonychia), dysphagia as a result of pharyngeal webs unusual dietary cravings (pica).

•The cause of the epithelial cell changes is not clear but may be related to reduction of iron in iron – containing enzymes.

•In children, iron deficiency is particularly significant as it can cause irritability, poor cognitive function and a decline in psychomotor development.

Figure 3.6

The development of iron deficiency anemia. Reticuloendothelial (macrophage) stores are lost completely before anemia develops. MCH, mean corpuscular hemoglobin; MCV, mean corpuscular volume.

Laboratory findings

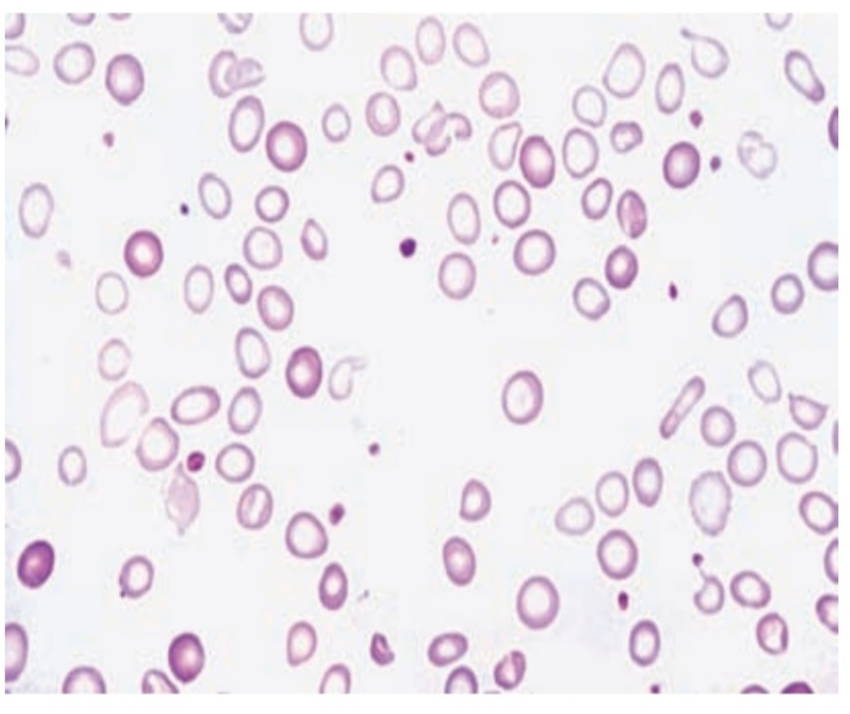

•Red cell indices and blood film:

•Even before anemia occurs, the red cell indices fall, and they fall progressively as the anemia becomes more severe.

•The blood film shows hypochromic microcytic cells with occasional target cells and pencil – shaped poikilocytes (Fig. 3.8 ).

•The reticulocyte count is low in relation to the degree of anemia.

•Figure 3.8

•The peripheral blood film in severe iron deficiency anemia.

•The cells are microcytic and hypochromic with occasional target cells.

•When iron deficiency is associated with severe folate or vitamin B 12 deficiency a ‘dimorphic ’ film occurs with a dual population of red cells of which one is macrocytic and the other microcytic and hypochromic; the indices may be normal.

•A dimorphic blood film is also seen in patients with iron deficiency anemia who have received recent iron therapy and produced a population of new haemoglobinized normal – sized red cells and when the patient has been transfused.

•The platelet count is often moderately raised in iron deficiency, particularly when hemorrhage is continuing.

•Bone marrow iron

•Bone marrow examination is not essential to assess iron stores except in complicated cases.

•In iron deficiency anemia there is a complete absence of iron from stores (macrophages) and from developing erythroblasts.

•The erythroblasts are small and have a ragged cytoplasm.

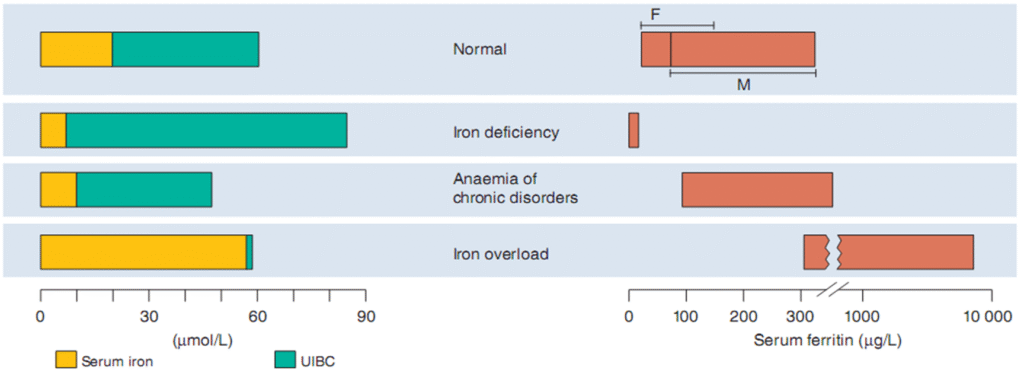

•Serum iron and total iron‐binding capacity:

•The serum iron falls and total iron‐binding capacity (TIBC) rises so that the TIBC is less than 20% saturated (Fig. 3.11).

•These contrasts both with the anemia of chronic disorders, when the serum iron and the TIBC are both reduced, and with other hypochromic anemias where the serum iron is normal or even raised.

•Serum ferritin:

•A small fraction of body ferritin circulates in the serum, the concentration being related to tissue, particularly reticuloendothelial, iron stores.

•The normal range in men is higher than in women (Fig. 3.11).

•In iron deficiency anemia the serum ferritin is very low while a raised serum ferritin indicates iron overload or excess release of ferritin from damaged tissues or an acute phase response (e.g. in inflammation).

•The serum ferritin is normal or raised in the anemia of chronic disorders.

Figure 3.11

•The serum iron, unsaturated serum iron‐binding capacity (UIBC) and serum ferritin in normal subjects and in those with iron deficiency, anemia of chronic disorders and iron overload.

•The total iron‐binding capacity (TIBC) is made up of the serum iron and the UIBC. In some laboratories, the transferrin content of serum is measured directly by immune diffusion, rather than by its ability to bind iron, and is expressed in g/L.

•Normal serum contains 2–4 g/L transferrin (1 g/L transferrin = 20 μmol/L binding capacity). Normal ranges for serum iron are 10–30 μmol/L; for TIBC, 40–75 μmol/L; for serum ferritin, male, 40–340 μg/L; female, 14–150 μg/L.

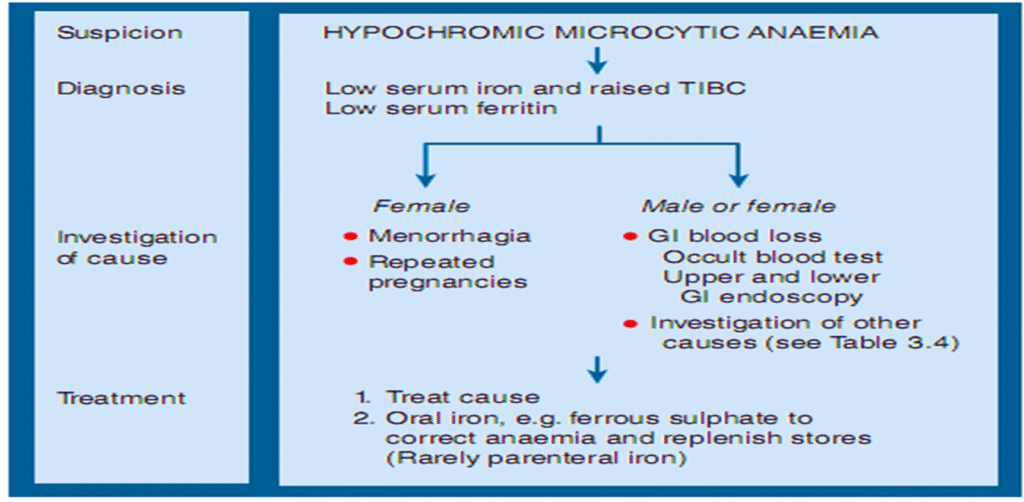

Investigation of the cause of iron deficiency (Fig. 3.12)

Treatment of iron deficiency Hypochromic anemia

•The underlying cause is treated as far as possible. In addition, iron is given to correct the anemia and replenish iron stores.

•Oral iron

•The best preparation is ferrous sulphate, which is cheap, contains 67 mg iron in each 200‐mg tablet and is best given on an empty stomach in doses spaced by at least 6 hours.

•Ferrous fumarate is equally cheap and effective.

•If side‐effects occur (e.g. nausea, abdominal pain, constipation or diarrhea), these can be reduced by giving iron with food or by using a preparation of lower iron content (e.g. ferrous gluconate which contains less iron (37 mg) per 300‐mg tablet).

•An elixir is available for children. Slow‐release preparations should not be used.

•Oral iron therapy should be given for long enough both to correct the anemia and to replenish body iron stores, which usually means for at least 6 months.

•The hemoglobin should rise at the rate of approximately 20 g/L every 3 weeks.

•Parenteral iron

•Parenteral iron therapy is occasionally necessary for patients intolerant or unresponsive to oral iron therapy, for receiving recombinant erythropoietin therapy, or for use in treating functional iron deficiency.

•There are now three parenteral iron products available:

•iron dextran,

•ferric gluconate,

•iron sucrose.

•We summarize the advantages and disadvantages of each product, including risk of anaphylaxis and hypersensitivity, dosage regimens, and costs.

•The increased availability of multiple parenteral iron preparations should decrease the need to use red cell transfusions in patients with iron-deficiency anemia.

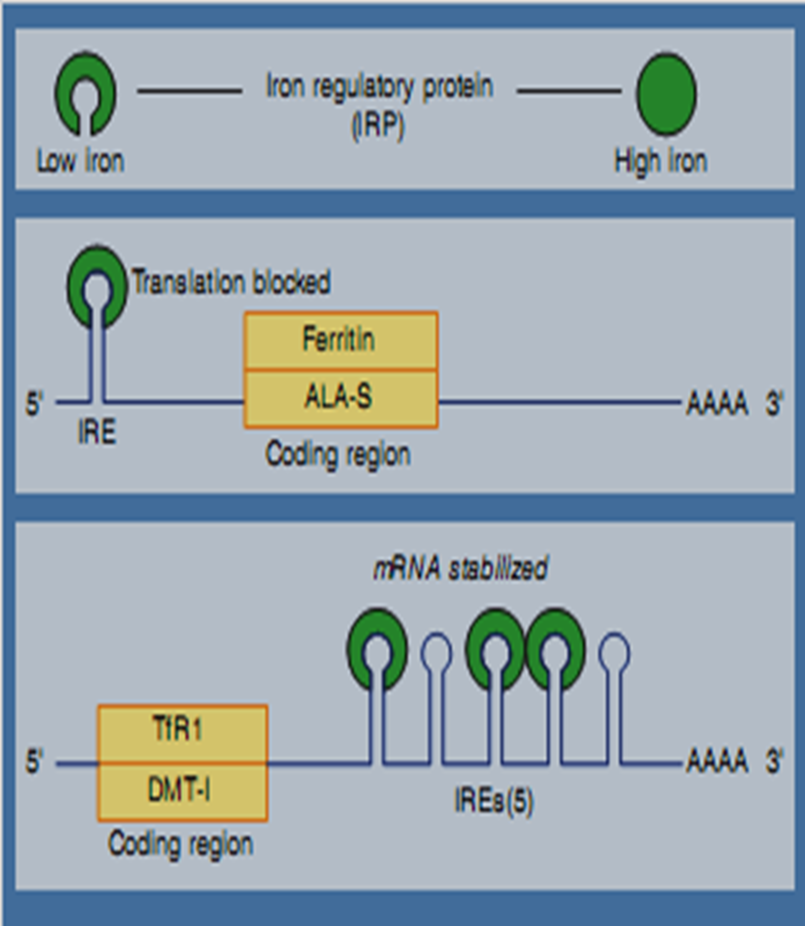

Anemia of chronic disorders