Red Blood Cells (Erythrocytes)

A major function of red blood cells, also known as erythrocytes, is to transport hemoglobin, which in turn carries oxygen from the lungs to the tissues.

In some lower animals, hemoglobin circulates as free protein in the plasma, not enclosed in red blood cells. When it is free in the plasma of the human being, about 3 percent of it leaks through the capillary membrane into the tissue spaces or through the glomerular membrane of the kidney into the glomerular filtrate each time the blood passes through the capillaries.

Therefore, hemoglobin must remain inside red blood cells to effectively perform its functions in humans.

The red blood cells have other functions besides transport of hemoglobin.

For instance, they contain a large quantity of carbonic anhydrase, an enzyme that catalyzes the reversible reaction between carbon dioxide (CO2) and water to form carbonic acid (H2CO3), increasing the rate of this reaction several thousand fold.

The rapidity of this reaction makes it possible for the water of the blood to transport enormous quantities of CO2 in the form of bicarbonate ion ( HCO3) from the tissues to the lungs, where it is reconverted to CO2 and expelled into the atmosphere as a body waste product.

The hemoglobin in the cells is an excellent acid-base buffer (as is true of most proteins), so the red blood cells are responsible for most of the acid-base buffering power of whole blood.

Shape and Size of Red Blood Cells

Normal red blood cells, shown in Figure 32-3, are biconcave discs having a mean diameter of about 7.8 micrometers and a thickness of 2.5 micrometers at the thickest point and 1 micrometer or less in the center . The average volume of the red blood cell is 90 to 95 cubic micrometers.

The shapes of red blood cells can change remarkably as the cells squeeze through capillaries. Actually , the red blood cell is a “bag” that can be deformed into almost any shape. Furthermore, because the normal cell has a great excess of cell membrane for the quantity of material inside, deformation does not stretch the membrane greatly and, consequently , does not rupture the cell, as would be the case with many other cells.

Concentration of Red Blood Cells in the Blood

In healthy men, the average number of red blood cells per cubic millimeter is 5,200,000 (±300,000); in women, it is 4,700,000 (±300,000).

Persons living at high altitudes have greater numbers of red blood cells, as discussed later.

Quantity of Hemoglobin in the Cells

Red blood cells have the ability to concentrate hemoglobin in the cell fluid up to about 34 grams in each 100 milliliters of cells.

The concentration does not rise above this value because this is the metabolic limit of the cell hemoglobin-forming mechanism.

Furthermore, in normal people, the percentage of hemoglobin is almost always near the maximum in each cell.

However, when hemoglobin formation is deficient, the percentage of hemoglobin in the cells may fall consider ably below this value and the volume of the red cell may also decrease because of diminished hemoglobin to fill the cell.

When the hematocrit (the percentage of blood that is in cells-normally, 40 to 45 percent) and the quantity of hemoglobin in each respective cell are normal,

The whole blood of men contains an average of 15 grams of hemoglobin per 100 milliliters of cells; for women, it contains an average of 14 grams per 100 milliliters.

As discussed in connection with blood transport of oxygen in Chapter 40, each gram of pure hemoglobin is capable of combining with 1.34 ml of oxygen.

Therefore, in a normal man a maximum of about 20 milliliters of oxygen can be carried in combination with hemoglobin in each 100 milliliters of blood, and in a normal woman 19 milliliters of oxygen can be carried.

Production of Red Blood Cells

Areas of the Body That Produce Red Blood Cells

In the early weeks of embryonic life, primitive, nucleated red blood cells are produced in the yolk sac.

During the middle trimester of gestation, the liver is the main organ for production of red blood cells, but reasonable numbers are also produced in the spleen and lymph nodes.

Then, during the last month or so of gestation and after birth, red blood cells are produced exclusively in the bone marrow.

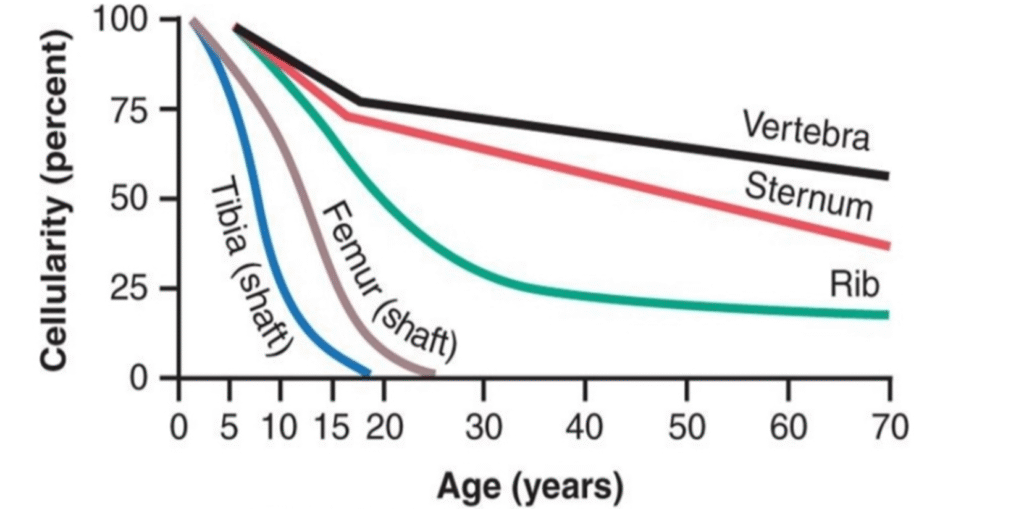

As demonstrated in Figure 32-1, the bone marrow of essentially all bones produces red blood cells until a person is 5 years old.

The marrow of the long bones, except for the proximal portions of the humeri and tibiae, becomes quite fatty and produces no more red blood cells after about age 20 years.

Beyond this age, most red cells continue to be produced in the marrow of the membranous bones, such as the vertebrae, sternum, ribs, and ilia.

Even in these bones, the marrow becomes less productive as age increases.

Genesis of Blood Cells

Pluripotential Hematopoietic Stem Cells, Growth Inducers, and Differentiation Inducers:

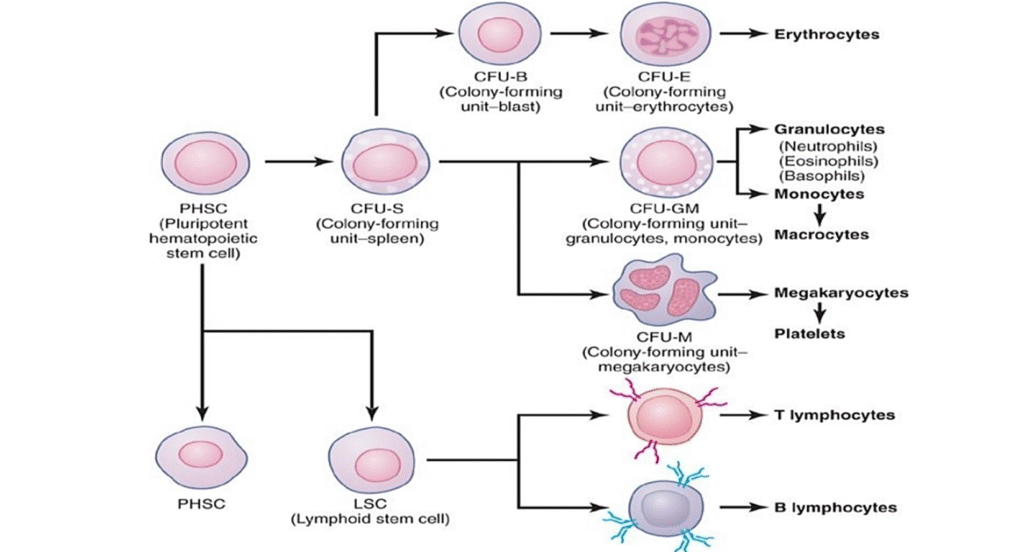

The blood cells begin their lives in the bone marrow from a single type of cell called the pluripotential hematopoietic stem cell, from which all the cells of the circulating blood are eventually derived.

Figure 32-2 shows the successive divisions of the pluripotential cells to form the different circulating blood cells.

As these cells reproduce, a small portion of them remains exactly like the original pluripotential cells and is retained in the bone marrow to maintain a supply of these, although their numbers diminish with age.

Most of the reproduced cells, however, differentiate to form the other cell types shown to the right in Figure 32-2.

The intermediate-stage cells are very much like the pluripotential stem cells, even though they have already become committed to a particular line of cells and are called committed stem cells.

The different committed stem cells, when grown in culture, will produce colonies of specific types of blood cells.

A committed stem cell that produces erythrocytes is called a colony-forming unit-erythrocyte, and the abbreviation CFU-E is used to designate this type of stem cell.

Likewise, colony-forming units that form granulocytes and monocytes have the designation CFU-GM and so forth.

Growth and reproduction of the different stem cells are controlled by multiple proteins called growth inducers. Four major growth inducers have been described, each having different characteristics.

One of these, interleukin-3, promotes growth and reproduction of virtually all the different types of committed stem cells, whereas the others induce growth of only specific types of cells.

The growth inducers promote growth but not differentiation of the cells. This is the function of another set of proteins called differentiation inducers.

Each of these causes one type of committed stem cell to differentiate one or more steps toward a final adult blood cell.

Formation of the growth inducers and differentiation inducers is itself controlled by factors outside the bone marrow.

For instance, in the case of erythrocytes (red blood cells), exposure of the blood to low oxygen for a long time causes growth induction, differentiation, and production of greatly increased numbers of erythrocytes, as discussed later in the chapter.

In the case of some of the white blood cells, infectious diseases cause growth, differentiation, and eventually formation of specific types of white blood cells that are needed to combat each infection.

Stages of Differentiation of Red Blood Cells

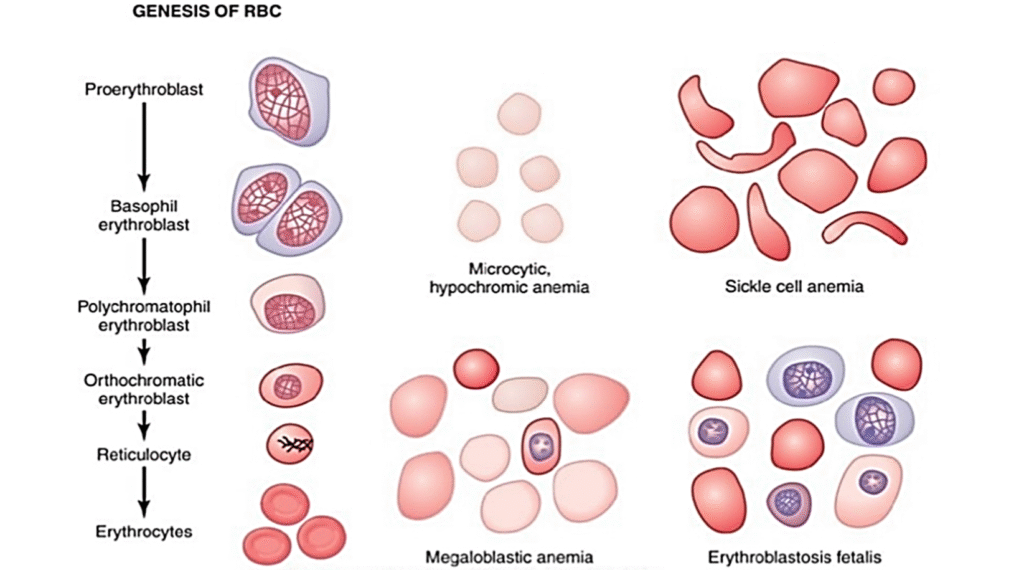

The first cell that can be identified as belonging to the red blood cell series is the pro-erythroblast, shown at the starting point in Figure 32-3.

Under appropriate stimulation, large numbers of these cells are formed from the CFU-E stem cells.

Once the pro-erythroblast has been formed, it divides multiple times, eventually forming many mature red blood cells.

The first-generation cells are called basophil erythroblasts because they stain with basic dyes; the cell at this time has accumulated very little hemoglobin.

In the succeeding generations, as shown in Figure 32-3, the cells become filled with hemoglobin to a concentration of about 34 percent, the nucleus condenses to a small size, and its final remnant is absorbed or extruded from the cell.

At the same time, the endoplasmic reticulum is also reabsorbed. The cell at this stage is called a reticulocyte because it still contains a small amount of basophilic material, consisting of remnants of the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and a few other cytoplasmic organelles.

During this reticulocyte stage, the cells pass from the bone marrow into the blood capillaries by diapedesis (squeezing through the pores of the capillary membrane).

The remaining basophilic material in the reticulocyte normally disappears within 1 to 2 days, and the cell is then a mature erythrocyte.

Because of the short life of the reticulocytes, their concentration among all the red cells of the blood is normally slightly less than 1 percent.

Regulation of Red Blood Cell

Production-Role of Erythropoietin

The total mass of red blood cells in the circulatory system is regulated within narrow limits, so

(1) adequate red cells are always available to provide sufficient transport of oxygen from the lungs to the tissues, yet

(2) the cells do not become so numerous that they impede blood flow.

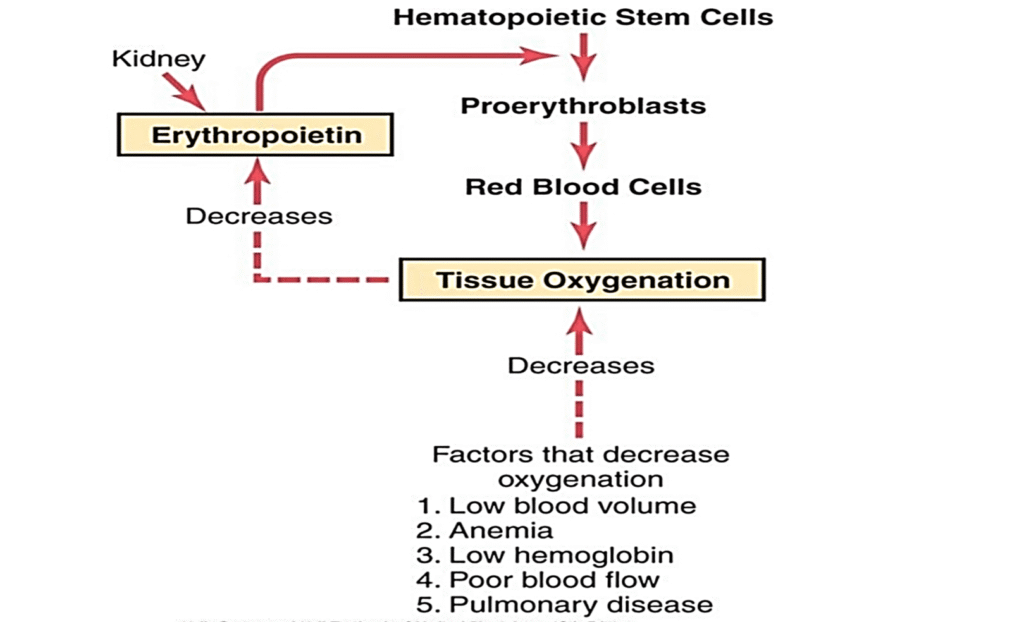

This control mechanism is diagrammed in Figure 32-4 and is as follows.

Tissue Oxygenation Is the Most Essential Regulator of Red Blood Cell Production

Any condition that causes the quantity of oxygen transported to the tissues to decrease ordinarily increases the rate of red blood cell production.

Thus, when a person becomes extremely anemic as a result of hemorrhage or any other condition, the bone marrow begins to produce large quantities of red blood cells.

Also, destruction of major portions of the bone marrow by any means, especially by x-ray therapy, causes hyperplasia of the remaining bone marrow, there by attempting to supply the demand for red blood cells in the body.

At very high altitudes, where the quantity of oxygen in the air is greatly decreased, insufficient oxygen is transported to the tissues and red cell production is greatly increased.

In this case, it is not the concentration of red blood cells in the blood that controls red cell production, but the amount of oxygen transported to the tissues in relation to tissue demand for oxygen.

Various diseases of the circulation that cause decreased tissue blood flow, and particularly those that cause failure of oxygen absorption by the blood as it passes through the lungs, can also increase the rate of red cell production.

This is especially apparent in prolonged cardiac failure and in many lung diseases because the tissue hypoxia resulting from these conditions increases red cell production, with a resultant increase in hematocrit and usually total blood volume as well.

Erythropoietin Stimulates Red Cell Production, and Its Formation Increases in Response to Hypoxia

The principal stimulus for red blood cell production in low oxygen states is a circulating hormone called erythropoietin, a glycoprotein with a molecular weight of about 34,000.uIn the absence of erythropoietin, hypoxia has little or no effect to stimulate red blood cell production.

But when the erythropoietin system is functional, hypoxia causes a marked increase in erythropoietin production and the erythropoietin in turn enhances red blood cell production until the hypoxia is relieved.

Role of the Kidneys in Formation of Erythropoietin

Normally, about 90 percent of all erythropoietin is formed in the kidneys; the remainder is formed mainly in the liver.

It is not known exactly where in the kidneys the erythropoietin is formed.

Some studies suggest that erythropoietin is secreted mainly by fibroblast-like interstitial cells surrounding the tubules in the cortex and outer medulla secrete, where much of the kidney’s oxygen consumption occurs.

It is likely that other cells, including the renal epithelial cells themselves, also secrete the erythropoietin in response to hypoxia.

Renal tissue hypoxia leads to increased tissue levels of hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1), which serves as a transcription factor for a large number of hypoxia-inducible genes, including the erythropoietin gene.

HIF-1 binds to a hypoxia response element residing in the erythropoietin gene, inducing transcription of mRNA and, ultimately, increased erythropoietin synthesis.

At times, hypoxia in other parts of the body, but not in the kidneys, stimulates kidney erythropoietin secretion, which suggests that there might be some nonrenal sensor that sends an additional signal to the kidneys to produce this hormone.

In particular, both norepinephrine and epinephrine and several of the prostaglandins stimulate erythropoietin production.

When both kidneys are removed from a person or when the kidneys are destroyed by renal disease, the person invariably becomes very anemic because the 10 percent of the normal erythropoietin formed in other tissues (mainly in the liver) is sufficient to cause only one third to one half the red blood cell formation needed by the body.

Effect of Erythropoietin in Erythro-genesis

When an animal or a person is placed in an atmosphere of low oxygen, erythropoietin begins to be formed within minutes to hours, and it reaches maximum production within 24 hours.

Yet almost no new red blood cells appear in the circulating blood until about 5 days later.

From this fact, as well as from other studies, it has been determined that the important effect of erythropoietin is to stimulate the production of pro-erythroblasts from hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow.

In addition, once the pro-erythroblasts are formed, the erythropoietin causes these cells to pass more rapidly through the different erythroblastic stages than they normally do, further speeding up the production of new red blood cells.

The rapid production of cells continues as long as the person remains in a low oxygen state or until enough red blood cells have been produced to carry adequate amounts of oxygen to the tissues despite the low oxygen;

At this time, the rate of erythropoietin production decreases to a level that will maintain the required number of red cells but not an excess.

In the absence of erythropoietin, few red blood cells are formed by the bone marrow.

At the other extreme, when large quantities of erythropoietin are formed and if there is plenty of iron and other required nutrients available, the rate of red blood cell production can rise to perhaps 10 or more times normal.

Therefore, the erythropoietin mechanism for controlling red blood cell production is a powerful one.

Maturation Failure Caused by Poor Absorption of VitaminB12 from the Gastrointestinal Tract

Pernicious Anemia

A common cause of red blood cell maturation failure is failure to absorb vitamin B12 from the gastrointestinal tract.

This often occurs in the disease pernicious anemia, in which the basic abnormality is an atrophic gastric mucosa that fails to produce normal gastric secretions.

The parietal cells of the gastric glands secrete a glycoprotein called intrinsic factor, which combines with vitamin B12 in food and makes the B12 available for absorption by the gut.

It does this in the following way:

(1) Intrinsic factor binds tightly with the vitamin B12. In this bound state, the B12 is protected from digestion by the gastrointestinal secretions.

(2) Still in the bound state, intrinsic factor binds to specific receptor sites on the brush border membranes of the mucosal cells in the ileum.

(3) Then, vitamin B12 is transported into the blood during the next few hours by the process of pinocytosis, carrying intrinsic factor and the vitamin together through the membrane.

Lack of intrinsic factor, therefore, decreases availability of vitamin B12 because of faulty absorption of the vitamin.

Failure of Maturation Caused by Deficiency of Folic Acid (Pteroylglutamic Acid)

Folic acid is a normal constituent of green vegetables, some fruits, and meats (especially liver).

However, it is easily destroyed during cooking.

Also, people with gastrointestinal absorption abnormalities, such as the frequently occurring small intestinal disease called sprue, often have serious difficulty absorbing both folic acid and vitamin B12.

Therefore, in many instances of maturation failure, the cause is deficiency of intestinal absorption of both folic acid and vitamin B12.