Introduction

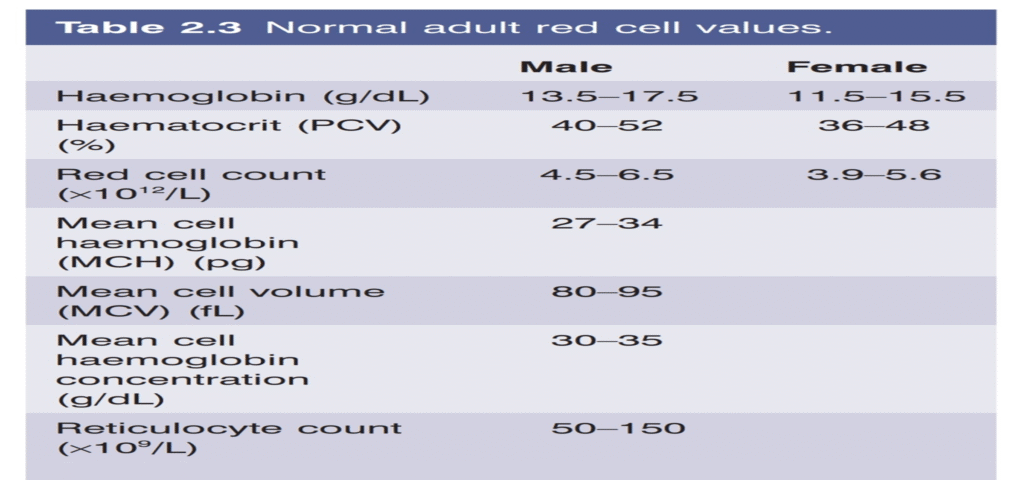

•Anemia is defined as a reduction in the hemoglobin concentration of the blood below normal for age and sex OR red cell defect (Table 2.3).

•Reduction of hemoglobin is usually accompanied by a fall in red cell count and packed cell volume (PCV), but these may be normal in some patients with subnormal hemoglobin levels (and therefore by definition anemic).

Clinical features of Anemia

•The presence or absence of clinical features can be considered under four major headings.

•1 Speed of onset: Rapidly progressive anemia causes more symptoms than anemia of slow onset because there is less time for adaptation in the cardiovascular system and in the O2 dissociation curve of hemoglobin.

•2 Severity: Mild anemia often produces no symptoms or signs, but these are usually present when the hemoglobin is less than 9 – 10 g/dL. Even severe anemia (hemoglobin concentration as low as 6.0 g/dL) may produce remarkably few symptoms, however, when there is very gradual onset in a young subject who is otherwise healthy.

•3 Age: The elderly tolerate anemia less well than the young because of the effect of lack of oxygen on organs when normal cardiovascular compensation (increased cardiac output caused by increased stroke volume and tachycardia) is impaired.

•4 Hemoglobin O2 dissociation curve: Anemia, in general, is associated with a rise in 2,3 – DPG in the red cells and a shift in the O2 dissociation curve to the right so that oxygen is given up more readily to tissues. This adaptation is particularly marked in some anemias that either affect red cell metabolism directly (e.g. pyruvate kinase deficiency which causes a rise in 2,3 – DPG concentration in the red cells) or that are associated with a low affinity hemoglobin (e.g. HbS) (Fig. 2.9).

Symptoms of Anemia

•Symptoms are:

•shortness of breath,

•particularly on exercise,

•weakness,

•lethargy,

•Palpitation

•headaches.

•In older patients,

•symptoms of cardiac failure

•angina pectoris or intermittent claudication or confusion may be present.

•Visual disturbances because of retinal hemorrhages may complicate very severe anemia, particularly of rapid onset.

Signs of Anemia

•These may be divided into general and specific.

•General signs include pallor of mucous membranes which occurs if the hemoglobin level is less than 9 – 10 g/dL (Fig. 2.14). Conversely, skin color is not a reliable sign.

•A hyperdynamic circulation may be present with tachycardia,

•a bounding pulse,

•cardiomegaly and a systolic flow murmur especially at the apex.

•Particularly in the elderly, features of congestive heart failure may be present.

•Retinal hemorrhages are unusual (Fig. 2.15)

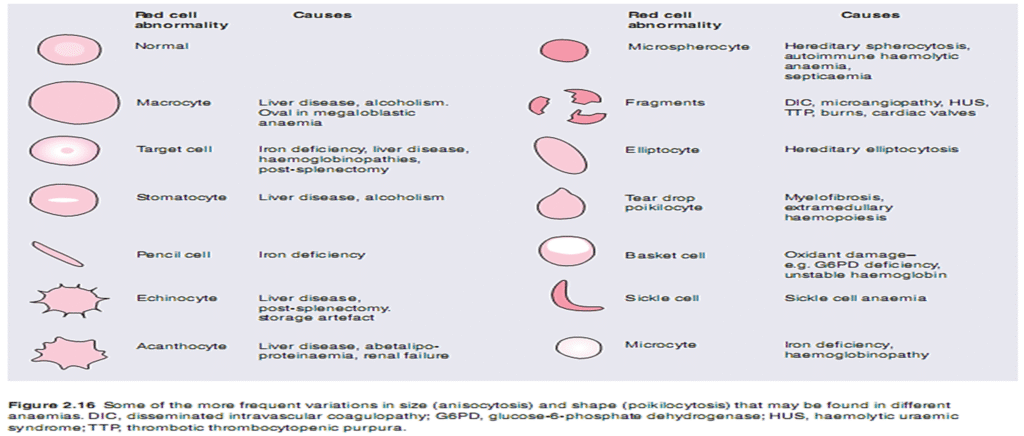

Specific signs are associated with particular types of anemia, e.g. koilonychia (spoon nails) with iron deficiency, jaundice with hemolytic or megaloblastic anemias, leg ulcers with sickle cell and other hemolytic anemias, bone deformities with thalassemia major.

Basis of Classification of Anemia

•Red cell indices

•Th e most useful classification is that based on red cell indices (Table 2.3) and divides the anemia into microcytic, normocytic and macrocytic (Table 2.4).

•As well as suggesting the nature of the primary defect, this approach may also indicate an underlying abnormality before overt anemia has developed.

•In two common physiological situations the mean corpuscular volume (MCV) may be outside the normal adult range. In the newborn for a few weeks the MCV is high but in infancy it is low (e.g. 70 FL at 1 year of age) and rises slowly through out childhood to the normal adult range.

•In normal pregnancy there is a slight rise in MCV, even in the absence of other causes of macrocytosis (e.g. folate deficiency).

•Leucocyte and platelet counts

•Measurement of these helps to distinguish ‘pure’ anemia from ‘pancytopenia’ (subnormal levels of red cells, neutrophils and platelets), which suggests a more general marrow defect or destruction of cells (e.g. hypersplenism).

•In anemias caused by hemolysis or hemorrhage, the neutrophil and platelet counts are often raised; in infections and leukemias, the leucocyte count is also often raised and there may be abnormal leucocytes or neutrophil precursors present.

•Reticulocyte count

•The normal percentage is 0.5–2.5%, and the absolute count 50–150 × 109/L (Table 2.4). This should rise in anemia because of erythropoietin increase and be higher the more severe the anemia.

•This is particularly so when there has been time for erythroid hyperplasia to develop in the marrow as in chronic hemolysis.

•After an acute major hemorrhage there is an erythropoietin response in 6 hours, the reticulocyte count rises within 2–3 days, reaches a maximum in 6–10 days and remains raised until the hemoglobin returns to the normal level.

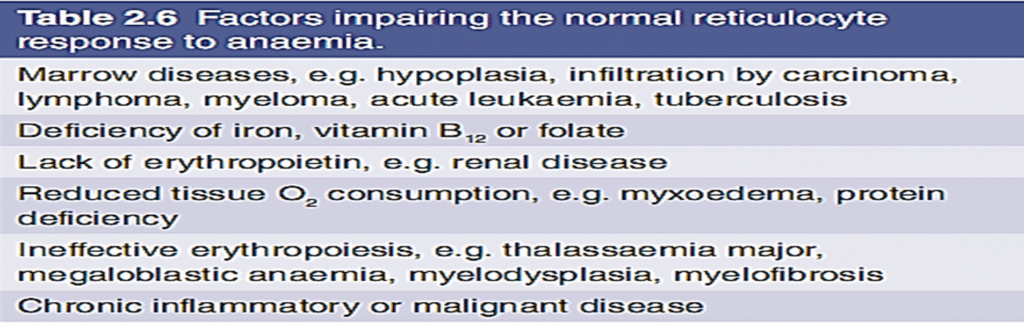

•If the reticulocyte count is not raised in an anemic patient this suggests impaired marrow function or lack of erythropoietin stimulus (Table 2.6).