Automatic Electrical Rhythmicity of the Sinus Fibers of heart

•Some cardiac fibers have the capability of self-excitation, a process that can cause automatic rhythmical discharge and contraction.

•This is especially true of the fibers of the heart’s specialized conducting system, including the fibers of the sinus node.

•For this reason, the sinus node ordinarily controls the rate of beat of the entire heart, as discussed in detail later in this chapter.

Sinus (Sinoatrial) Node of heart

•The sinus node (also called sino atrial node) is a small, flattened, ellipsoid strip of specialized cardiac muscle about 3 millimeters wide, 15 millimeters long, and1 millimeter thick.

•It is located in the superior posterolateral wall of the right atrium immediately below and slightly lateral to the opening of the superior vena cava.

Mechanism of Sinus Nodal Rhythmicity in heart

•The “resting membrane potential” of the sinus nodal fiber between discharges has a negativity of about -55 to -60 millivolts, in comparison with -85 to -90 millivolts for the ventricular muscle fiber.

•They are (1) fast sodium channels, (2) slow sodium calcium channels, and (3) potassium channels.

•Opening of the fast sodium channels for a few 10,000ths of a second is responsible for the rapid upstroke spike of the action potential observed in ventricular muscle, because of rapid influx of positive sodium ions to the interior of the fiber.

•Then the “environment” of the ventricular action potential is caused primarily by slower opening of the slow sodium-calcium channels, which lasts for about 0.3 second.

•Finally, opening of potassium channels allows diffusion of large amounts of positive potassium ions in the outward direction through the fiber membrane and returns the membrane potential to its resting level.

Self-Excitation of Sinus Nodal Fibers

•Because of the high sodium ion concentration in the extracellular fluid outside the nodal fiber, as well as a moderate number of already open sodium channels, positive sodium ions from outside the fibers normally tend to leak to the inside.

•When the potential reaches a threshold voltage of about -40 millivolts, the sodium-calcium channels become “activated,” thus causing the action potential.

Why does this leakiness to sodium and calcium ions not cause the sinus nodal fibers to remain depolarized all the time?

•Two events occur during the course of the action potential to prevent this.

•First, the sodium-calcium channels become inactivated (i.e., they close) within about 100 to 150 milliseconds after opening, and second, at about the same time, greatly increased numbers of potassium channels open.

•Therefore, influx of positive calcium and sodium ions through the sodium-calcium channels ceases, while at the same time large quantities of positive potassium ions diffuse out of the fiber. Both of these effects reduce the intracellular potential back to its negative resting level and therefore terminate the action potential.

why is this new state of hyperpolarization not maintained forever?

•The reason is that during the next few tenths of a second after the action potential is over, progressively more and more potassium channels close.

•The inward-leaking sodium and calcium ions once again overbalance the outward flux of potassium ions, and this causes the “resting” potential to drift upward once more, finally reaching the threshold level for discharge at a potential of about -40 millivolts.

•Then the entire process begins again: self-excitation to cause the action potential, recovery from the action potential, hyperpolarization after the action potential is over, drift of the “resting” potential to threshold, and finally re-excitation to elicit another cycle.

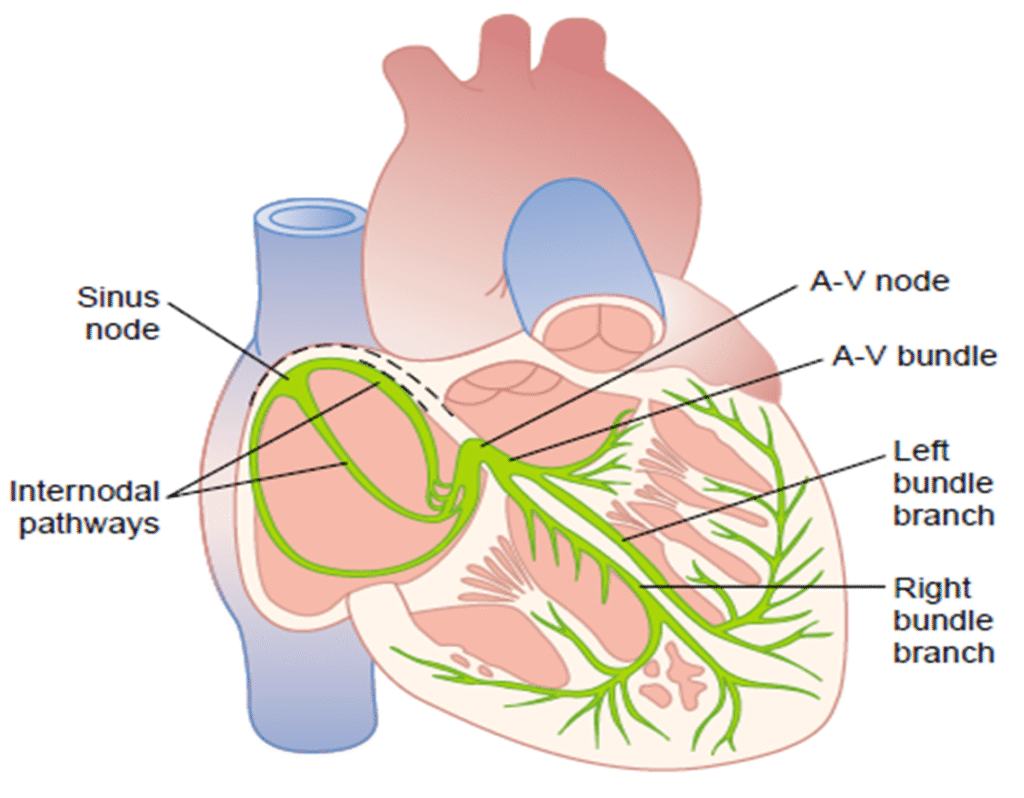

Internodal Pathways and Transmission of the Cardiac Impulse Through the Atria

•The ends of the sinus nodal fibers connect directly with surrounding atrial muscle fibers. Therefore, action potentials originating in the sinus node travel outward into these atrial muscle fibers.

•The velocity of conduction in most atrial muscle is about 0.3 m/sec, but conduction is more rapid, about 1 m/sec, in several small bands of atrial fibers.

•One of these, called the anterior interatrial band, passes through the anterior walls of the atria to the left atrium.

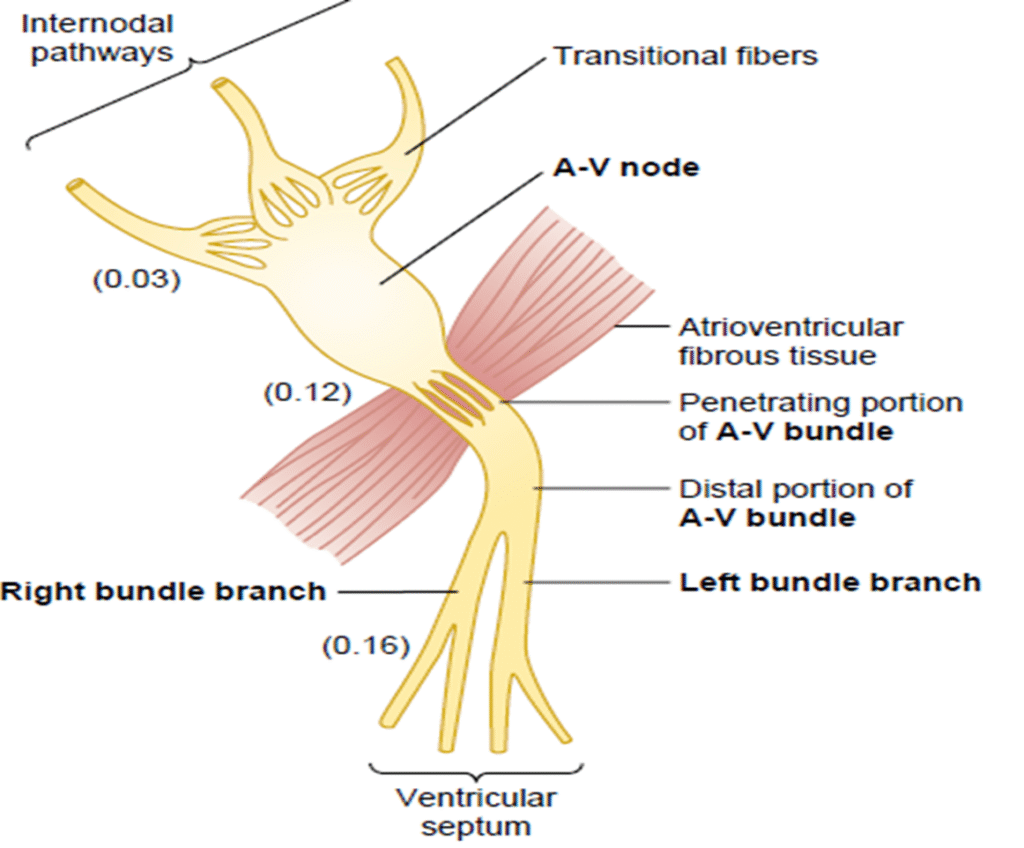

•In addition, three other small bands curve through the anterior, lateral, and posterior atrial walls and terminate in the A-V node; shown in Figures 10–1 and 10–3, these are called, respectively, the anterior, middle, and posterior internodal pathways.

Atrioventricular Node, and Delay of Impulse Conduction from the Atria to the Ventricles

•The atrial conductive system is organized so that the cardiac impulse does not travel from the atria into the ventricles too rapidly; this delay allows time for the atria to empty their blood into the ventricles before ventricular contraction begins. It is primarily the A-V node and its adjacent conductive fibers that delay this transmission into the ventricles.

•Thus, the total delay in the A-V nodal and A-V bundle system is about 0.13 second.

•This, in addition to the initial conduction delay of 0.03 second from the sinus node to the A-V node, makes a total delay of 0.16 second before the excitatory signal finally reaches the contracting muscle of the ventricles.

Cause of the Slow Conduction

•The slow conduction in the transitional, nodal, and penetrating A-V bundle fibers is caused mainly by diminished numbers of gap junctions between successive cells in the conducting pathways, so that there is great resistance to conduction of excitatory ions from one conducting fiber to the next.

•Therefore, it is easy to see why each succeeding cell is slow to be excited.

Rapid Transmission in the Ventricular Purkinje System

•Special Purkinje fibers lead from the A-V node through the A-V bundle into the ventricles.

•They are very large fibers, even larger than the normal ventricular muscle fibers, and they transmit action potentials at a velocity of 1.5 to 4.0 m/sec, a velocity about 6 times that in the usual ventricular muscle and 150 times that in some of the A-V nodal fibers.

•The rapid transmission of action potentials by Purkinje fibers is believed to be caused by a very high level of permeability of the gap junctions at the intercalated discs between the successive cells that make up the Purkinje fibers and their small sizes.

One-Way Conduction Through the A-V Bundle

•A special characteristic of the A-V bundle is the inability, except in abnormal states, of action potentials to travel backward from the ventricles to the atria. This prevents re-entry of cardiac impulses by this route from the ventricles to the atria, allowing only forward conduction from the atria to the ventricles.

Distribution of the Purkinje Fibers in the Ventricles—The Left and Right Bundle Branches

•After penetrating the fibrous tissue between the atrial and ventricular muscle, the distal portion of the A-V bundle passes downward in the ventricular septum for 5 to 15 millimeters toward the apex of the heart.

•Then the bundle divides into left and right bundle branches that lie beneath the endocardium on the two respective sides of the ventricular septum.

•Each branch spreads downward toward the apex of the ventricle, progressively dividing into smaller branches.

•These branches in turn course sidewise around each ventricular chamber and back toward the base of the heart.

•The ends of the Purkinje fibers penetrate about one third the way into the muscle mass and finally become continuous with the cardiac muscle fibers.

Transmission of the Cardiac (heart) Impulse in the Ventricular Muscle

•Once the impulse reaches the ends of the Purkinje fibers, it is transmitted through the ventricular muscle mass by the ventricular muscle fibers themselves.

•The velocity of transmission is now only 0.3 to 0.5 m/sec, one sixth that in the Purkinje fibers.

•The cardiac muscle wraps around the heart in a double spiral, with fibrous septa between the spiraling layers; therefore, the cardiac impulse does not necessarily travel directly outward toward the surface of the heart but instead angulates toward the surface along the directions of the spirals.

•Because of this, transmission from the endocardial surface to the epicardial surface of the ventricle requires as much as another 0.03 second, approximately equal to the time required for transmission through the entire ventricular portion of the Purkinje system. Thus, the total time for transmission of the cardiac impulse from the initial bundle branches to the last of the ventricular muscle fibers in the normal heart is about 0.06 second.

Reference

Animal physiology by Eckert,4th edition