Nerve Action Potential

Nerve signals are transmitted by action potentials, which are rapid changes in the membrane potential that spread rapidly along the nerve fiber membrane.

Each action potential begins with a sudden change from the normal resting negative membrane potential to a positive potential and then ends with an almost equally rapid change back to the negative potential.

Stages of nerve action potential

Resting Stage. This is the resting membrane potential before the action potential begins. The membrane is said to be “polarized” during this stage because of the –90 millivolts negative membrane potential that is present.

Depolarization Stage. At this time, the membrane suddenly becomes very permeable to sodium ions, allowing tremendous numbers of positively charged sodium ions to diffuse to the interior of the axon.

The normal “polarized” state of –90 millivolts is immediately neutralized by the inflowing positively charged sodium ions, with the potential rising rapidly in the positive direction. This is called depolarization.

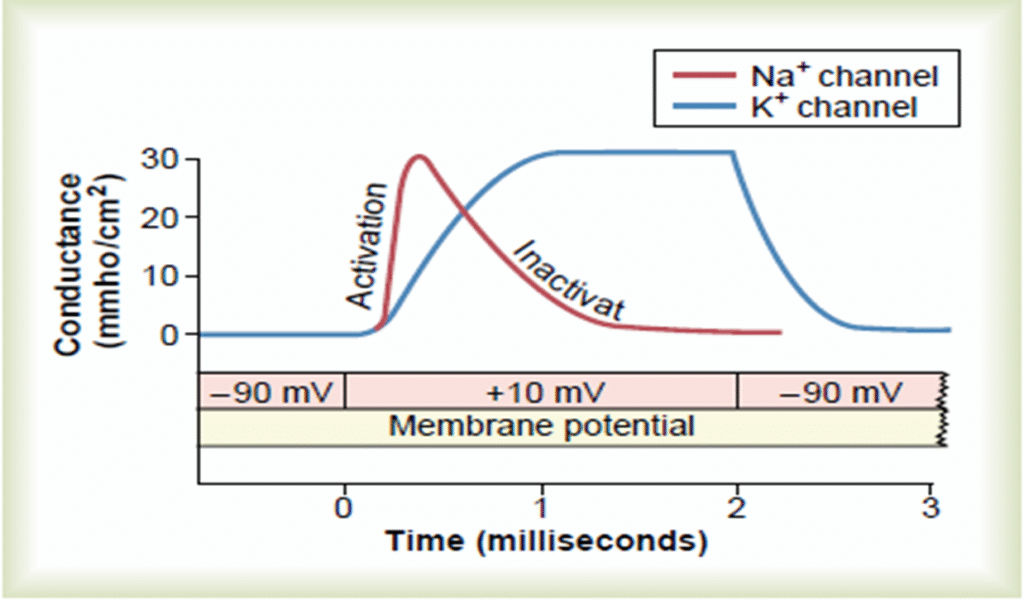

Repolarization Stage. Within a few 10,000ths of a second after the membrane becomes highly permeable to sodium ions, the sodium channels begin to close, and the potassium channels open more than normal. Then, rapid diffusion of potassium ions to the exterior re-establishes the normal negative resting membrane potential. This is called repolarization of the membrane.

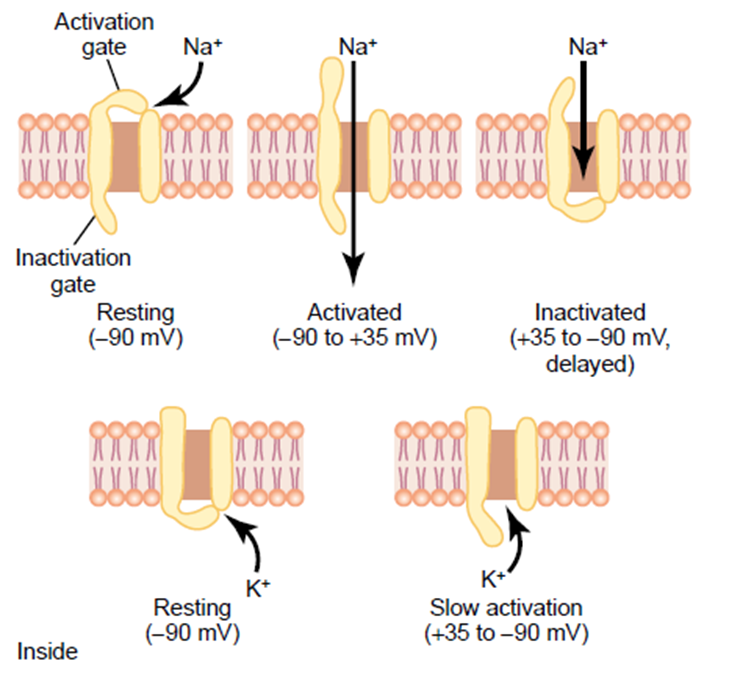

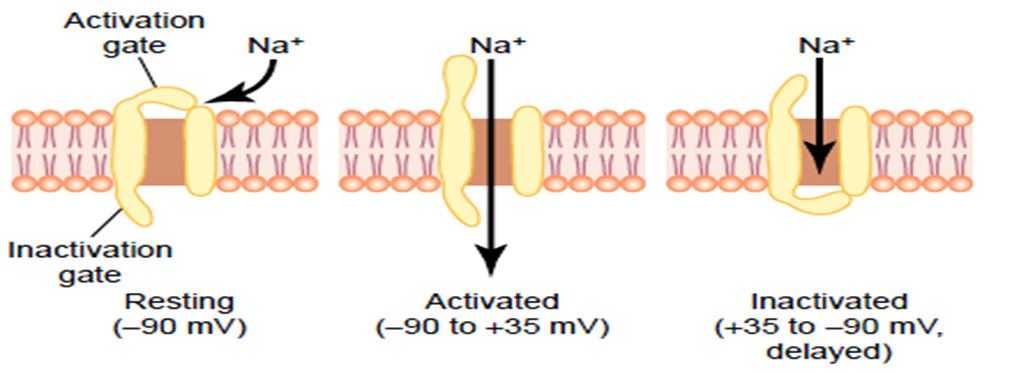

Voltage-Gated Sodium and Potassium Channel

Activation of the Sodium Channel

When the membrane potential becomes less negative than during the resting state.

It finally reaches a voltage usually somewhere between –70 and –50 millivolts that causes a sudden conformational change in the activation gate, flipping it all the way to the open position.

This is called the activated state; during this state, sodium ions can pour inward through the channel, increasing the sodium permeability of the membrane as much as 500- to 5000-fold.

Inactivation of the Sodium Channel

The same increase in voltage that opens the activation gate also closes the inactivation gate. The inactivation gate, however, closes a few 10,000ths of a second after the activation gate opens. That is, the conformational change that flips the inactivation gate to the closed state is a slower process than the conformational change that opens the activation gate.

Therefore, after the sodium channel has remained open for a few 10,000ths of a second, the inactivation gate closes, and sodium ions no longer can pour to the inside of the membrane.

At this point, the membrane potential begins to recover back toward the resting membrane state, which is the repolarization process.

Why didn’t Na+ channels reopen before repolarization of nerve fibers?

Another important characteristic of the sodium channel inactivation process is that the inactivation gate will not reopen until the membrane potential returns to or near the original resting membrane potential level.

Therefore, it usually is not possible for the sodium channels to open again without the nerve fiber’s first repolarizing.

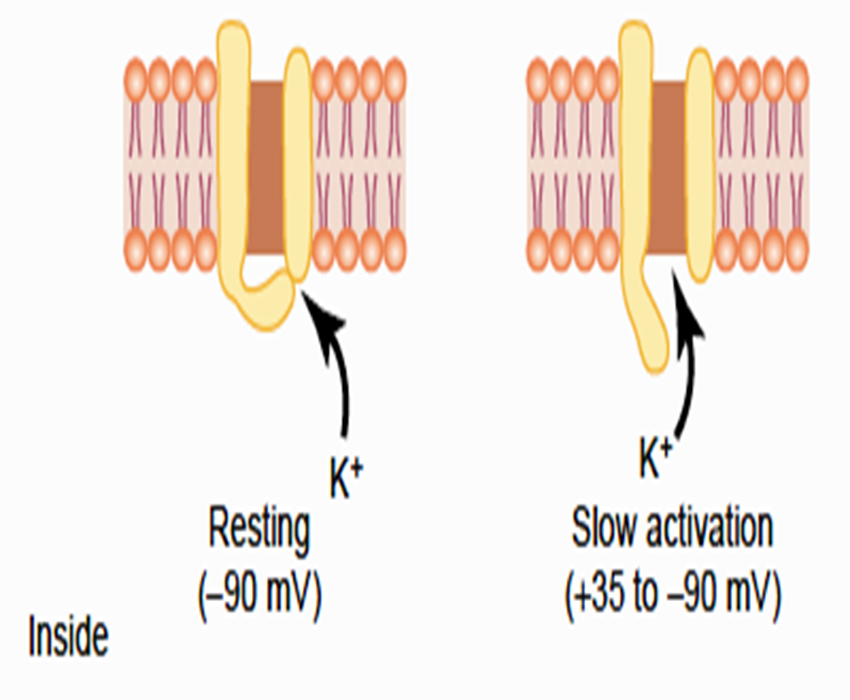

Activation of Potassium Channel

During the resting state, the gate of the potassium channel is closed, and potassium ions are prevented from passing through this channel to the exterior.

When the membrane potential rises from –90 millivolts toward zero, this voltage change causes a conformational opening of the gate and allows increased potassium diffusion outward through the channel.

However, because of the slight delay in opening of the potassium channels, for the most part, they open just at the same time that the sodium channels are beginning to close because of inactivation.

Thus, the decrease in sodium entry to the cell and the simultaneous increase in potassium exit from the cell combine to speed the repolarization process, leading to full recovery of the resting membrane potential within another few 10,000ths of a second.

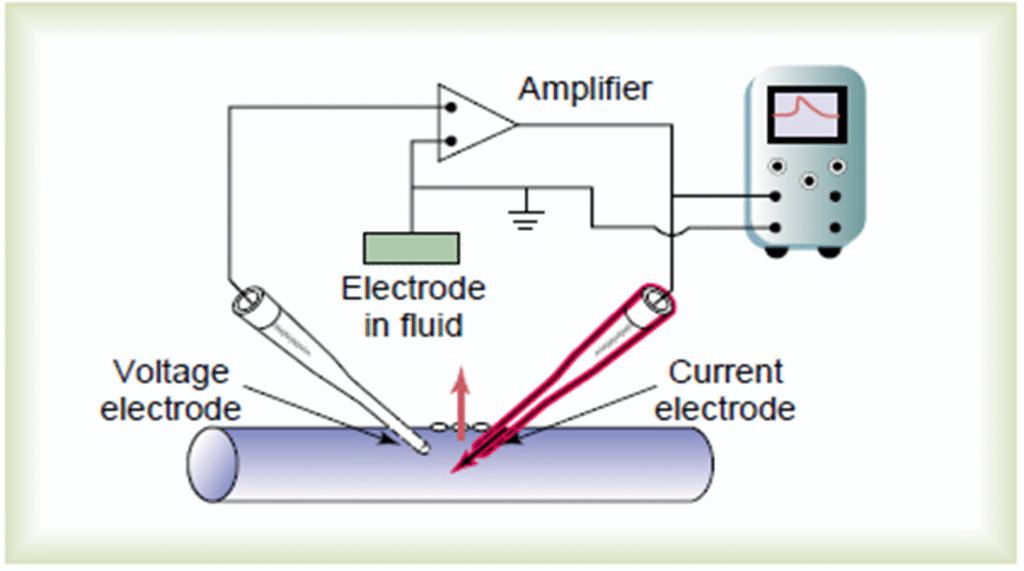

Measuring the effect of voltage gated channels

Roles of Other Ions During the Action Potential

Impermeant Negatively Charged Ions (Anions) Inside the Nerve Axon.

Inside the axon are many negatively charged ions include the anions of protein molecules and of many organic phosphate compounds, sulfate compounds, and so forth that cannot go through the membrane channels.

They are in excess inside the fibers.

Therefore, these negative ions are responsible for the negative charge inside the fiber.

Calcium Ions.

The membranes of almost all cells of the body have a calcium pump similar to the sodium pump, and calcium serves along with (or instead of) sodium in some cells to cause most of the action potential.

The calcium pump pumps calcium ions from the interior to the exterior of the cell membrane or into the endoplasmic reticulum of the cell. There are voltage-gated calcium channels.

These channels are slightly permeable to sodium ions as well as to calcium ions; when they open, both calcium and sodium ions flow to the interior of the fiber. Therefore, these channels are also called Ca++-Na+ channels.

The calcium channels are slow to become activated, requiring 10 to 20 times as long for activation as the sodium channels. Therefore, they are called slow channels, in contrast to the sodium channels, which are called fast channels.

Propagation of the Action Potential

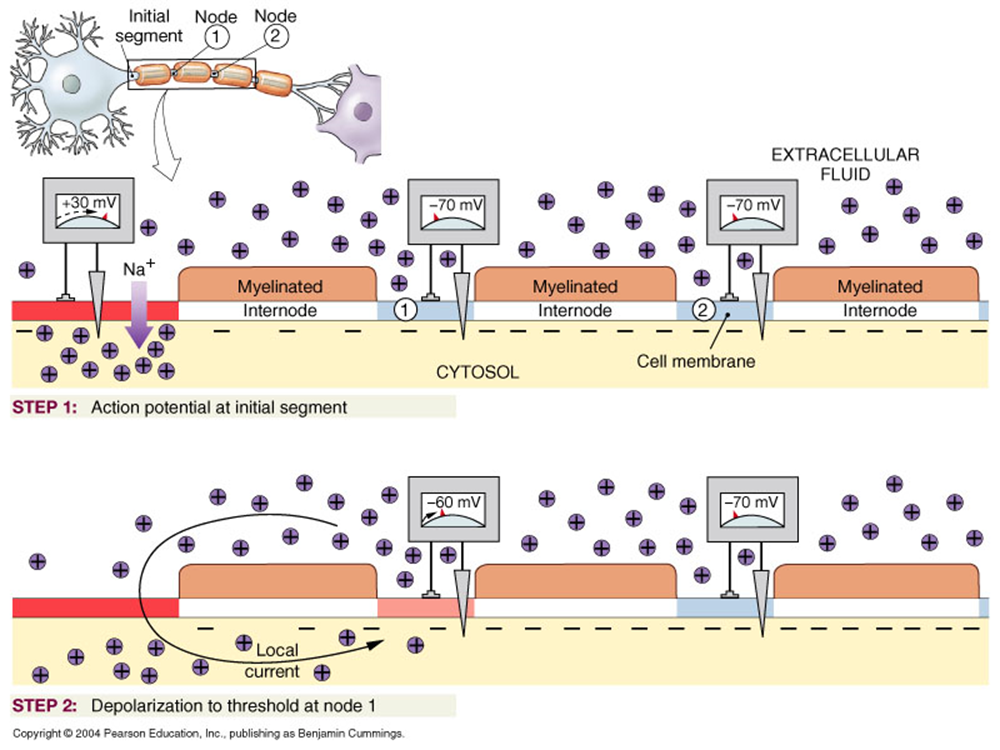

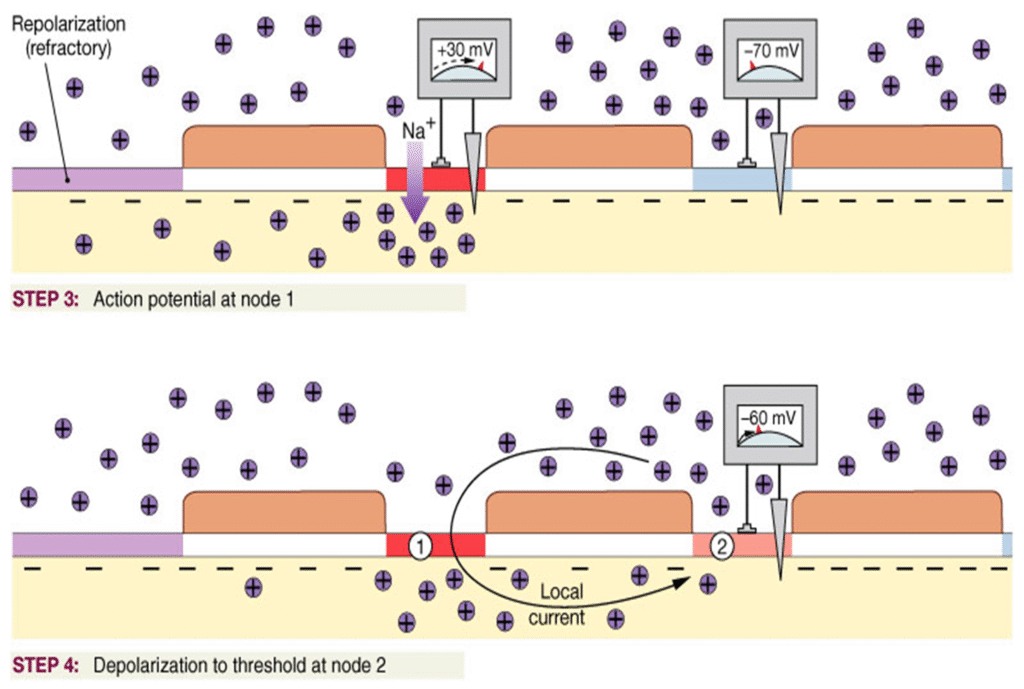

An action potential elicited at any one point on an excitable membrane usually excites adjacent portions of the membrane, resulting in propagation of the action potential along the membrane.

The sodium channels open in adjacent portion of cell membrane allow the inward movement of sodium ions increase depolarization on both sides. These positive charges increase the voltage for a distance of 1 to 3 millimeters above the threshold voltage value for initiating an action potential.

Propagation of an Action Potential along an Unmyelinated Axon

Saltatory Propagation along a Myelinated Axon

Direction of Propagation.

An excitable membrane has no single direction of propagation, but the action potential travels in all directions away from the stimulus even along all branches of a nerve fiber until the entire membrane has become depolarized.

All-or-Nothing Principle.

Once an action potential has been elicited at any point on the membrane of a normal fiber, the depolarization process travels over the entire membrane if conditions are right, or it does not travel at all if conditions are not right. This is called the all-or-nothing principle

Characteristics of action potentials

Generation of action potential follows all-or-none principle.

Refractory period lasts from time action potential begins until normal resting potential returns.

Continuous propagation

Spread of action potential across entire membrane in series of small steps.

salutatory propagation

Action potential spreads from node to node, skipping internodal membrane.

Action potential spreads from node to node, skipping internodal membrane

Muscle tissue has higher resting potential.

Muscle tissue action potentials are longer lasting.

Muscle tissue has slower propagation of action potentials.

Nerve impulse.

Action potential travels along an axon.

Information passes from presynaptic neuron to postsynaptic cell.

References

Animal physiology by Eckert, 4th edition.