Introduction to hormonal control of metamorphosis

•The control of metamorphosis by thyroid hormones was first demonstrated in 1912 by Gudernatsch, who discovered that tadpoles metamorphosed prematurely when fed powdered horse thyroid glands.

•In a complementary study, Allen (1916) found that when he removed or destroyed the thyroid rudiment of early tadpoles (thyroidectomy), the larvae never metamorphosed but instead grew into giant tadpoles.

•Subsequent studies showed that the sequential steps of anuran metamorphosis are regulated by increasing amounts of thyroid hormone.

•Some events (such as the development of limbs) occur early, when the concentration of thyroid hormones is low; other events (such as the resorption of the tail and remodeling of the intestine) occur later, after the hormones have reached higher concentrations.

•These observations gave rise to a threshold model , wherein the different events of metamorphosis are triggered by different concentrations of thyroid hormones .

•Although the threshold model remains useful, molecular studies have shown that the timing of the events of amphibian metamorphosis is more complex than just increasing hormone concentrations.

The metamorphic changes of frog development are brought about by,

•(1) the secretion of the hormone thyroxine (T4) into the blood by the thyroid gland;

•(2) the conversion of T4 into the more active hormone, triodothyronine (T3) by the target tissues;

•(3) the degradation of T3 in the target tissues.

•T3 binds to the nuclear thyroid hormone receptors (TRs) with much higher affinity than does T4, and causes these receptors to become transcriptional activators of gene expression.

•Thus, the levels of both T3 and TRs in the target tissues are essential for producing the metamorphic response in each tissue.

•The concentration of T3 in each tissue is regulated by the concentration of T3 in the blood and by two critical intracellular enzymes that remove iodine atoms from T4 and T3.

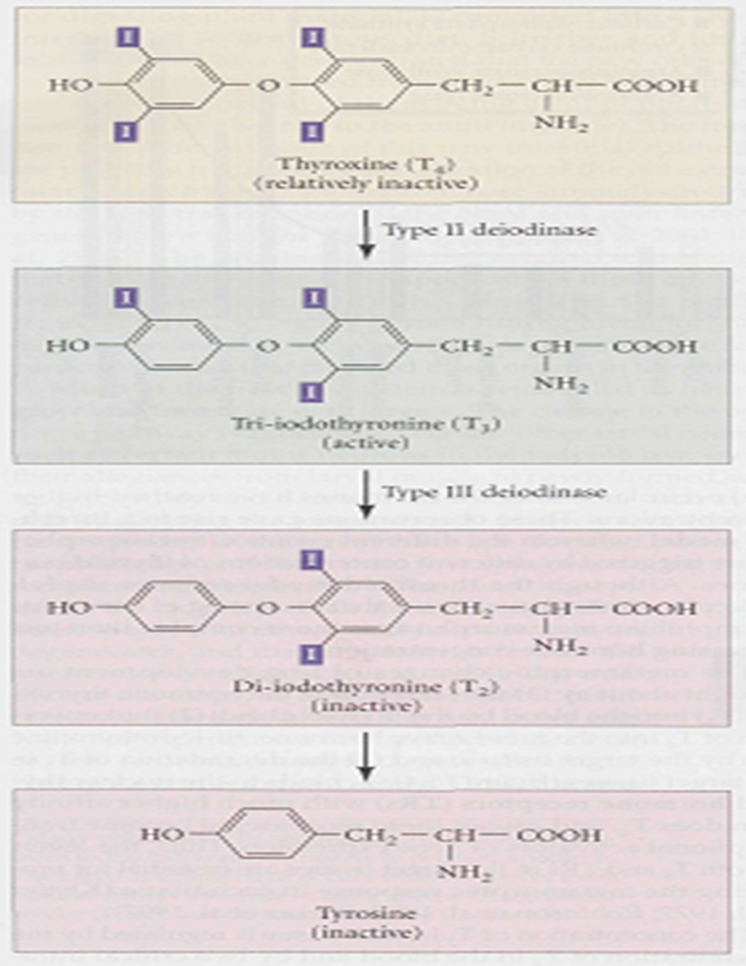

•Type II deiodinase removes an iodine atom from the outer ring of the precursor hormone (T4) to conver t it into the more active hormone T3.

•Type III deiodinase removes an iodine atom from the inner ring of T3 to convert it into an inactive compound that will eventually be metabolized to tyrosine.

•Tadpoles that are genetically modified to overexpress type III deiodinase in their target tissues never complete metamorphosis.

•Metabolism of thyroxine (T4) and tri-iodothyronine (T3).

•T4 serves as a prohormone.

•It is converted in the peripheral tissues to the active hormoneT3 by deiodinase II.

•T3 can be inactivated by deiodinase III, which converts T3 into diiodothyronine and then to tyrosine.

Types of Thyroid Hormone Receptors

•There are two types of thyroid hormone receptors. In Xenopus, thyroid hormone receptor α (TRα) is widely distributed throughout all tissues and is present even before the organism has a thyroid gland.

•Thyroid hormone receptor ß (TR ß ), however, is the product of a gene that is directly activated by thyroid hormones. TR ß levels are very low before the advent of metamorphosis; as the levels of thyroid hormone increase during metamorphosis, so do the intracellular levels of TR ß.

Thyroid hormone Receptors- TRs association

•The thyroid hormone receptors do not work alone, however, but form dimers with the retinoid receptor, RXR. These dimers bind thyroid hormones and can affect transcription.

•The TR-RXR complex appears to be physically associated with appropriate promoters and enhancers even before it binds T3.

•In its unbound state, the TR-RXR is a transcriptional repressor, recruiting histone deacetylases to the region of these genes. However, when T3 is added to the complex, the T3-TR-RXR complex activates those same genes by recruiting histone acetyltransferases.

Stages of metamorphosis on Concentration of thyroid hormones

•Metamorphosis is often divided into stages based on the concentration of thyroid hormones in circulation.

•During the first stage, pre-metamorphosis, the thyroid gland has begun to mature and is secreting low levels of T4 (and very low levels of T3).

•The initiation of T4 secretion may be brought about by corticotropin- releasing hormone (CRH, which in mammals initiates the stress response).

•CRH may act directly on the frog pituitary, instructing it to release thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), or it may act generally to make the body cells responsive to low amounts of T3.

•The tissues that respond earliest to the thyroid hormones are those that express high levels of deiodinase II, and can thereby convert T4 directly into T3.

•For instance, the limb rudiments, which have high levels of both deiodinase II and TRα, can convert T4 into T3 and use it immediately through the TRα receptor. Thus, during the early stage of metamorphosis, the limb rudiments are able to receive thyroid hormone and use it to start leg growth.

•As the thyroid matures to the stage of Pro metamorphosis, it secretes more thyroid hormones.

•However , many major changes (such as tail resorption, gill resorption, and intestinal remodeling) must wait until the metamorphic climax stage.

•At that time, the concentration of T4 rises dramatically, and TR ß levels peak inside the cells. Since one of the target genes of T3 is the TR ß gene, TR ß may be the principal receptor that mediates the metamorphic climax.

•In the tail, there is only a small amount of TRα during premetamorphosis , and deiodinase II is not detectable then.

•However, during Pro metamorphosis, the rising levels of thyroid hormones induce higher levels of TR ß.

•At metamorphic climax, deiodinase II is expressed, and the tail begins to be resorbed.

• In this way, the tail undergoes absorption only after the legs are functional (otherwise, the poor amphibian would have no means of locomotion).

•The wisdom of the frog is simple: never get rid of your tail before your legs are working.

•The frog brain also undergoes changes during metamorphosis, and one of the brain’s functions is to downregulate metamorphosis once metamorphic climax has been reached.

•Thyroid hormones eventually induce a negative feedback loop, shutting down the pituitary cells that instruct the thyroid to secrete them.

•Huang and colleagues (2001) have shown that, at the climax of metamorphosis, deiodinase II expression is seen in those cells of the anterior pituitary that secrete thyrotropin, the hormone that activates thyroid hormone expression.

•The resulting T3 suppresses transcription of the thyrotropin gene, thereby initiating the negative feedback loop so that less thyroid hormone is made.

Regionally specific developmental programs

•By regulating the amount of T3 and TRs in their cells, the different regions of the body can respond to thyroid hormones at different times.

•The type of response (proliferation, apoptosis, differentiation, migration) is determined by other factors already present in the different tissues.

•The same stimulus causes some tissues to degenerate while stimulating others to develop and differentiate, as exemplified by the process of tail degeneration. Thus, thyroid hormone instructs the limb bud muscles to grow (they die without thyroxine) while instructing the tail muscles to undergo apoptosis.

•The resorption of the tadpole’s tail structures is brought about by apoptosis and is relatively rapid, since the bony skeleton does not extend to the tail.

•After apoptosis has taken place, macrophages collect in the tail region and digest the debris with their enzymes, especially collagenases and metalloproteinases.

•The result is that the tail becomes a large sac of proteolytic enzymes.

•The tail epidermis acts differently than the head or trunk epidermis. During metamorphic climax, the larval skin is instructed to undergo apoptosis.

•The tadpole head and body are able to generate a new epidermis from epithelial stem cells. The tail epidermis, however, lacks these stem cells and fails to generate new skin.

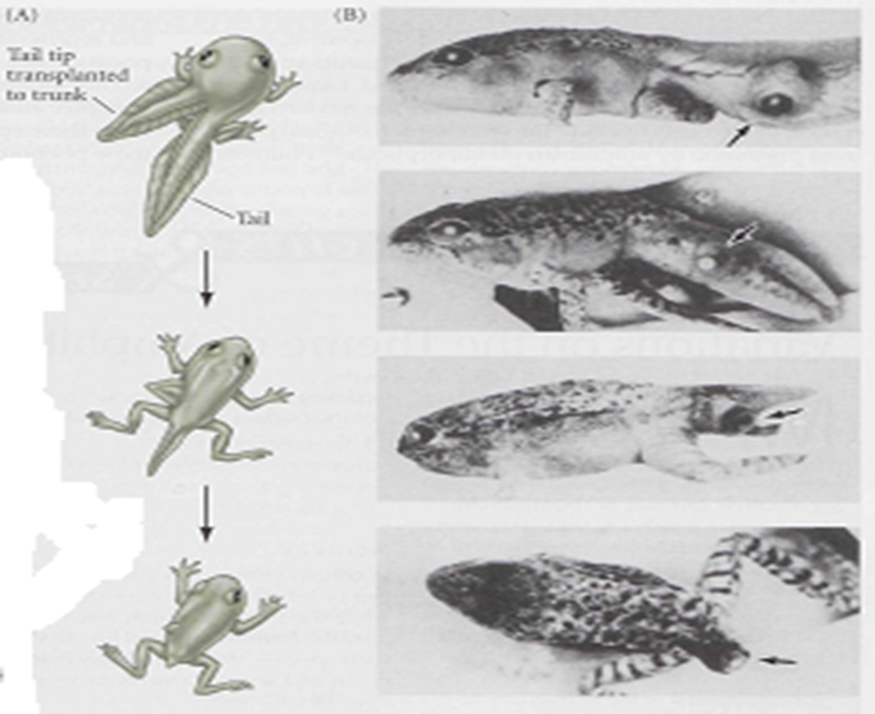

•Organ-specific responses to thyroid hormones have been dramatically demonstrated by transplanting a tail tip to the trunk region and by placing an eye cup in the tail.

•Tail tip tissue placed in the trunk is not protected from degeneration, but the eye cup retains its integrity despite the fact that it lies within the degenerating tail.

•Thus, the degeneration of the tail represents an organ-specific programmed cell death response, and only specific tissues die when the signal is given.

•Such programmed cell deaths are important in molding the body.

•Regional specificity during frog metamorphosis.

•(A) Tail tips regress even when transplanted into the trunk.

•(B) Eye cups remain intact even when transplanted into the regressing tail.

References

Developmental biology, 9th edition, by Scott F. Gilbert