Introduction

•Environmental law, principles, policies, directives, and regulations enacted and enforced by local, national, or international entities to regulate human treatment of the nonhuman world.

•The vast field covers a broad range of topics in diverse legal settings, such as state bottle-return laws in the United States, regulatory standards for emissions from coal-fired power plants in Germany, initiatives in China to create a “Green Great Wall”—a shelter belt of trees—to protect Beijing from sandstorms, and international treaties for the protection of biological diversity and the ozonosphere.

•During the late 20th century environmental law developed from a modest adjunct of the law of public health regulations into an almost universally recognized independent field protecting both human health and nonhuman nature.

Levels Of Environmental Law

•Environmental law exists at many levels and is only partly constituted by international declarations, conventions, and treaties.

•The bulk of environmental law is statutory—i.e., encompassed in the enactments of legislative bodies—and regulatory—i.e., generated by agencies charged by governments with protection of the environment.

•In addition, many countries have included some right to environmental quality in their national constitutions.

•Since 1994, for example, environmental protection has been enshrined in the German (“Basic Law”), which now states that the government must protect for “future generations the natural foundations of life.”

•Similarly, the Chinese constitution declares that the state “ensures the rational use of natural resources and protects rare animals and plants”

•The South African constitution recognizes a right to “an environment that is not harmful to health or well-being; and to have the environment protected, for the benefit of present and future generations”

•The Bulgarian constitution provides for a “right to a healthy and favorable environment, consistent with stipulated standards and regulations”

•The Chilean constitution contains a “right to live in an environment free from contamination.”

Types Of Environmental Law

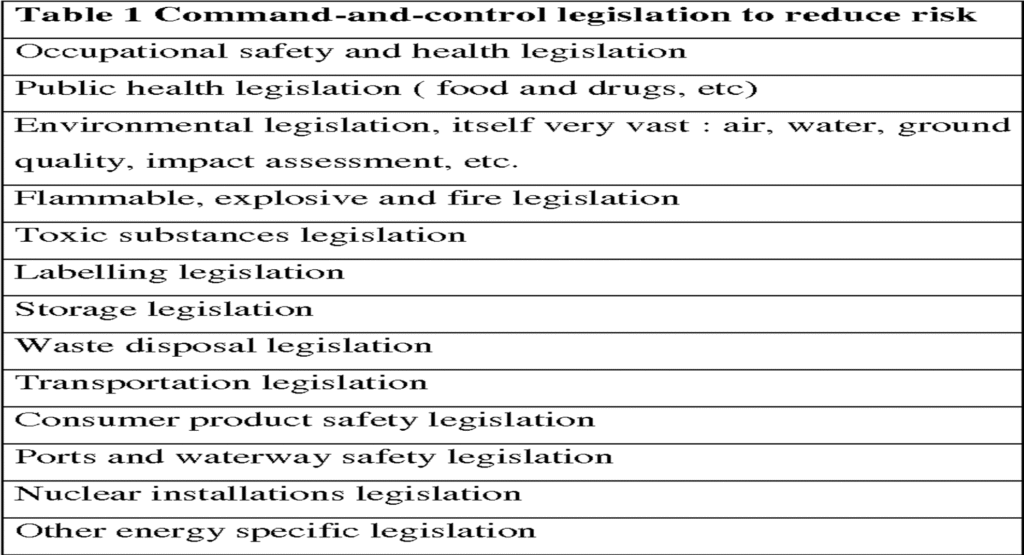

•Command-and-control legislation:

•Most environmental law falls into a general category of laws known as “command and control.”

•Such laws typically involve three elements:

•(1) identification of a type of environmentally harmful activity,

• (2) imposition of specific conditions or standards on that activity, and

• (3) prohibition of forms of the activity that fail to comply with the imposed conditions or standards.

•The United States Federal Water Pollution Control Act (1972), for example, regulates “discharges” of “pollutants” into “navigable waters of the United States.”

•All three terms are defined in the statute and agency regulations and together identify the type of environmentally harmful activity subject to regulation.

•In 1983 Germany passed a national emission-control law that set specific air emission thresholds by power plant age and type.

•Almost all environmental laws prohibit regulated activities that do not comply with stated conditions or standards. Many make a “knowing” (intentional) violation of such standards a crime.

•The most obvious forms of regulated activity involve actual discharges of pollutants into the environment (e.g., air, water, and groundwater pollution).

•However, environmental laws also regulate activities that entail a significant risk of discharging harmful pollutants (e.g., the transportation of hazardous waste, the sale of pesticides, and logging).

•For actual discharges, environmental laws generally prescribe specific thresholds of allowable pollution; for activities that create a risk of discharge, environmental laws generally establish management practices to reduce that risk.

•Standards Imposed On Actual Discharges

•The standards imposed on actual discharges generally come in two forms:

• (1) environmental-quality, or ambient, standards, which fix the maximum amount of the regulated pollutant or pollutants tolerated in the receiving body of air or water, and (2) emission, or discharge, standards, which regulate the amount of the pollutant or pollutants that any “source” may discharge into the environment.

•Most comprehensive environmental laws impose both Environmental-quality and Discharge Standards and endeavor to coordinate their use to achieve a stated environmental-quality goal.

•Environmental-quality goals can be either numerical or narrative. Numerical targets set a specific allowable quantity of a pollutant (e.g., 10 micrograms of carbon monoxide per cubic meter of air measured over an eight-hour period).

•Another type of activity regulated by command-and-control legislation is environmentally harmful trade. Among the most developed regulations are those on trade in wildlife. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES, 1973), for example, authorizes signatories to the convention to designate species “threatened with extinction which are or may be affected by trade.”

Environmental assessment mandates

•Environmental assessment mandates are another significant form of environmental law.

•Such mandates generally perform three functions:

• (1) identification of a level or threshold of potential environmental impact at which a contemplated action is significant enough to require the preparation of an assessment,

• (2) establishment of specific goals for the assessment mandated, and

• (3) setting of requirements to ensure that the assessment will be considered in determining whether to proceed with the action as originally contemplated or to pursue an alternative action.

•Unlike command-and-control regulations, which may directly limit discharges into the environment, mandated environmental assessments protect the environment indirectly by increasing the quantity and quality of publicly available information on the environmental consequences of contemplated actions.

•This information potentially improves the decision making of government officials and increases the public’s involvement in the creation of environmental policy.

•Such assessments must describe and evaluate the direct and indirect effects of the project on humans, fauna, flora, soil, water, air, climate, and landscape and the interaction between them.

Economic incentives

•The use of economic instruments to create incentives for environmental protection is a popular form of environmental law.

•Such incentives include pollution taxes, subsidies for clean technologies and practices, and the creation of markets in either environmental protection or pollution.

•Denmark, The Netherlands, and Sweden, for example, impose taxes on carbon dioxide emissions, and the EU has debated whether to implement such a tax at the supranational level to combat climate change.

•In the United States, water pollution legislation passed in 1972 provided subsidies to local governments to upgrade publicly owned sewage treatment plants.

•In 1980 the U.S. government, prompted in part by the national concern inspired by industrial pollution in the Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls,

•New York created a federal “superfund” that used general revenues and revenue from taxes on petrochemical feedstocks, crude oil, and general corporate income to finance the clean-up of more than 1,000 sites polluted by hazardous substances.

•By the 1990s, “tradable allowance schemes”, which permit companies to buy and sell “pollution credits,” or legal rights to produce specified amounts of pollution, had been implemented in the United States.

•The most comprehensive and complex such program, created as part of the 1990 Clean Air Act, was designed to reduce overall sulfur dioxide emissions by fossil-fuel-fired power plants.

•According to proponents, the program would provide financial rewards to cleaner plants, which could sell their unneeded credits on the market, and allow dirtier plants to stay in business while they converted to cleaner technologies.

Set-aside schemes

•A final method of environmental protection is the setting aside of lands and waters in their natural state.

•In the United States, for example, the vast majority of the land owned by the federal government (about one-third of the total land area of the country) can be developed only with the approval of a federal agency.

•Europe has an extensive network of national parks and preserves on both public and private land, and there are extensive national parks in southern and eastern Africa in which wildlife is protected.

•Arguably, the large body of law that regulates use of public lands and publicly held resources is “environmental law.” Some, however, maintain that it is not.

•Many areas of law can be characterized as both “set aside” and regulatory. For example, international efforts to preserve wetlands have focused on setting aside areas of ecological value, including wetlands, and on regulating their use.

•The Ramsar Convention provides that wetlands are a significant “economic, cultural, scientific and recreational” resource, and a section of the Clean Water Act, the primary U.S. law for the protection of wetlands, contains a prohibition against unpermitted discharges of “dredge and fill material” into any “waters of the United States.”

Principles Of Environmental Law

•The design and application of modern environmental law have been shaped by a set of principles and concepts outlined in publications such as Our Common Future (1987), published by the World Commission on Environment and Development, and the Earth Summit’s Rio Declaration (1992).

The Precautionary Principle

•As discussed above, environmental law regularly operates in areas complicated by high levels of scientific uncertainty.

•In the case of many activities that entail some change to the environment, it is impossible to determine precisely what effects the activity will have on the quality of the environment or on human health.

•It is generally impossible to know, for example, whether a certain level of air pollution will result in an increase in mortality from respiratory disease,

•Whether a certain level of water pollution will reduce a healthy fish population, or whether oil development in an environmentally sensitive area will significantly disturb the native wildlife.

•The precautionary principle requires that, if there is a strong suspicion that a certain activity may have environmentally harmful consequences, it is better to control that activity now rather than to wait for incontrovertible scientific evidence.

•This principle is expressed in the Rio Declaration, which stipulates that, where there are “threats of serious or irreversible damage, lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation.”

•In the United States the precautionary principle was incorporated into the design of habitat-conservation plans required under the aegis of the Endangered Species Act.

•In 1989 the EC invoked the precautionary principle when it banned the importation of U.S. hormone-fed beef, and in 2000 the organization adopted the principle as a “full-fledged and general principle of international law.”

•In 1999 Australia and New Zealand invoked the precautionary principle in their suit against Japan for its alleged overfishing of southern bluefin tuna.

The Prevention Principle

•Although much environmental legislation is drafted in response to catastrophes, preventing environmental harm is cheaper, easier, and less environmentally dangerous than reacting to environmental harm that already has taken place. The prevention principle is the fundamental notion behind laws regulating the generation, transportation, treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste and laws regulating the use of pesticides.

•The principle was the foundation of the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and their Disposal (1989), which sought to minimize the production of hazardous waste and to combat illegal dumping.

•The prevention principle also was an important element of the EC’s Third Environmental Action Programmed, which was adopted in 1983.

The “Polluter Pays” Principle

•Since the early 1970s the “polluter pays” principle has been a dominant concept in environmental law. Many economists claim that much environmental harm is caused by producers who “externalize” the costs of their activities.

•For example, factories that emit unfiltered exhaust into the atmosphere or discharge untreated chemicals into a river pay little to dispose of their waste. Instead, the cost of waste disposal in the form of pollution is borne by the entire community.

•Similarly, the driver of an automobile bears the costs of fuel and maintenance but externalizes the costs associated with the gases emitted from the tailpipe. Accordingly, the purpose of many environmental regulations is to force polluters to bear the real costs of their pollution, though such costs often are difficult to calculate precisely.

•In theory, such measures encourage producers of pollution to make cleaner products or to use cleaner technologies.

•The “polluter pays” principle underlies U.S. laws requiring the cleanup of releases of hazardous substances, including oil. One such law, the Oil Pollution Act (1990), was passed in reaction to the spillage of some 11 million gallons (41 million liters) of oil into Prince William Sound in Alaska in 1989.

•The “polluter pays” principle also guides the policies of the EU and other governments throughout the world.

The integration principle

•Environmental protection requires that due consideration be given to the potential consequences of environmentally fateful decisions.

•Various jurisdictions (e.g., the United States and the EU) and business organizations (e.g., the U.S. Chamber of Commerce) have integrated environmental considerations into their decision-making processes through environmental-impact-assessment mandates and other provisions.

The public participation principle

•Decisions about environmental protection often formally integrate the views of the public.

•Generally, government decisions to set environmental standards for specific types of pollution,

•to permit significant environmentally damaging activities, or

•to preserve significant resources are made only after the impending decision has been formally and publicly announced and the public has been given the opportunity to influence the decision through written comments or hearings.

Sustainable development

•Sustainable development is an approach to economic planning that attempts to foster economic growth while preserving the quality of the environment for future generations.

•Despite its enormous popularity in the last two decades of the 20th century, the concept of sustainable development proved difficult to apply in many cases, primarily because the results of long-term sustainability analyses depend on the particular resources focused upon.

•For example, a forest that will provide a sustained yield of timber in perpetuity may not support native bird populations, and a mineral deposit that will eventually be exhausted may nevertheless support more or less sustainable communities.

•Sustainability was the focus of the 1992 Earth Summit and later was central to a multitude of environmental studies.

Current Trends and Prospects

•Although numerous international environmental treaties have been concluded, effective agreements remain difficult to achieve for a variety of reasons.

•Because environmental problems ignore political boundaries, they can be adequately addressed only with the cooperation of numerous governments, among which there may be serious disagreements on important points of environmental policy.

•Furthermore, because the measures necessary to address environmental problems typically result in social and economic hardships in the countries that adopt them, many countries, particularly in the developing world, have been reluctant to enter into environmental treaties.

•Since the 1970s a growing number of environmental treaties have incorporated provisions designed to encourage their adoption by developing countries.

•Such measures include financial cooperation, technology transfer, and differential implementation schedules and obligations.

•The greatest challenge to the effectiveness of environmental treaties is compliance.

•Although treaties can attempt to enforce compliance through mechanisms such as sanctions, such measures usually are of limited usefulness, in part because countries in compliance with a treaty may be unwilling or unable to impose the sanctions called for by the treaty.

•In general, the threat of sanctions is less important to most countries than the possibility that by violating their international obligations they risk losing their good standing in the international community.

•Enforcement mechanisms other than sanctions have been difficult to establish, usually because they would require countries to cede significant aspects of their national sovereignty to foreign or international organizations.

•In most agreements, therefore, enforcement is treated as a domestic issue, an approach that effectively allows each country to define compliance in whatever way best serves its national interest.

•Despite this difficulty, international environmental treaties and agreements are likely to grow in importance as international environmental problems become more acute.