1-Cleavage

•Fertilization of the chick egg occurs in the oviduct, before the albumen and shell are secreted to cover it.

•Like the egg of the zebrafish, the chick egg is telolecithal, with a small disc of cytoplasm—the blastodisc(zygote)—sitting atop a large yolk.

•Like fish eggs, the yolky eggs of birds undergo discoidal meroblastic cleavage.

•Cleavage occurs only in the blastodisc, which is about 2-3 mm in diameter and is located at the animal pole of the egg.

•The first cleavage furrow appears centrally in the blastodisc; other cleavages follow to create a single-layered blastoderm (Figure 8.1).

•As in the fish embryo, the cleavages do not extend into the yolky cytoplasm, so the early-cleavage cells are continuous with one another and with the yolk at their bases.

•Thereafter, equatorial and vertical cleavages divide the blastoderm into a tissue 5-6 cell layers thick, and the cells become linked together by tight junctions.

•Between the blastoderm and the yolk of avian eggs is a space called the subgerminal cavity, which is created when the blastoderm cells absorb water from the albumen (“egg white”)(hydrostatic pressure) and secrete the fluid between themselves and the yolk.

•At this stage, the deep cells in the center of the blastoderm appear to be shed and die, leaving behind a 1-cell-thick area pellucida; this part of the blastoderm forms most of the actual embryo.

•The peripheral ring of blastoderm cells that have not shed their deep cells constitutes the area opaca. Between the area pellucida and the area opaca is a thin layer of cells called the marginal zone (or marginal belt*).

•Some marginal zone cells become very important in determining cell fate during early chick development.

•Discoidal meroblastic cleavage in a chick egg.

•Avian eggs include some of the largest cells known to science (inches across), but cleavage takes place in only a small region, the blastodisc.

•(A-D) Four stages viewed from the animal pole (the future dorsal side of the embryo).

•(E) An early-cleavage embryo viewed from the side.

2-Gastrulation of the Avian Embryo

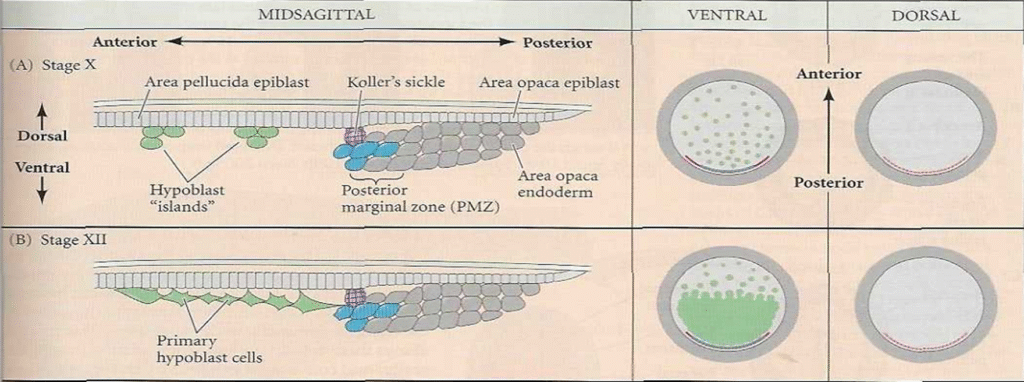

•The hypoblast

•By the time a hen has laid an egg, the blastoderm contains some 20,000 cells.

•At this time, most of the cells of the area pellucida remain at the surface, forming an “upper layer,” called the epiblast, while other area pellucida cells have delaminated and migrated individually into the sub germinal cavity to form hypoblast islands (sometimes called the primary hypoblast or Poly invagination islands), an archipelago of disconnected clusters of 5-20 cells each.

•Shortly thereafter, a sheet of cells derived from deep yolky cells at the posterior margin of the blastoderm migrates anteriorly beneath the surface.

•This sheet of migrating cells pushes the hypoblast islands anteriorly, thereby forming the secondary hypoblast, or endoblast (Figure 8.2B-E)

•The resulting two-layered blastoderm (epiblast and hypoblast) is joined together at the marginal zone of the area opaca, and the space between the layers forms a blastocoel.

•Thus, although the shape and formation of the avian blastodisc differ from those of the amphibian, fish, or echinoderm blastula, the overall spatial relationships are retained.

•The amniotes have evolved is a set of extra-embryonic tissues; the hypoblast, the yolk sac, and the amnion.

•The avian embryo comes entirely from the epiblast; the hypoblast does not contribute any cells to the developing embryo.

Functions of Hypoblast:

•1-The hypoblast cells form portions of the external membranes, especially the yolk sac and the stalk linking the yolk mass to the endodermal digestive tube.

•2-Hypoblast cells also provide chemical signals that specify the migration of epiblast cells.(paracrine signalling)

•However, the three germ layers of the embryo proper (plus the amnion) are formed solely from the epiblast.

•(A-C) Events prior lo laying of the shelled egg,

•(A) Stage X embryo, where islands of hypoblast cells can be seen, as well as a congregation of hypoblast cells around Koller’s sickle.

•(B) By stage XII just prior to primitive streak formation the hypoblast island cell has coalesced to form the primary hypoblast layer, which meets endoblast cells and primitive streak cells at Koller’s sickle.

•C) By stage XIII, the secondary hypoblast cells migrate anteriorly.

•(D) By stage 2 (6-7 hours after the egg is laid), the primitive streak cells form a third layer that lies between the hypoblast and epiblast cells.

•(E) By stage 3 (up to 13 hours post laying), the primitive streak has become a definitive region of the epiblast, with cells migrating through it to become the mesoderm and endoderm.

The primitive streak

•The major structural characteristic of avian, reptilian, and mammalian gastrulation is the primitive streak;* the primitive streak becomes the blastopore lips of amniote embryos.

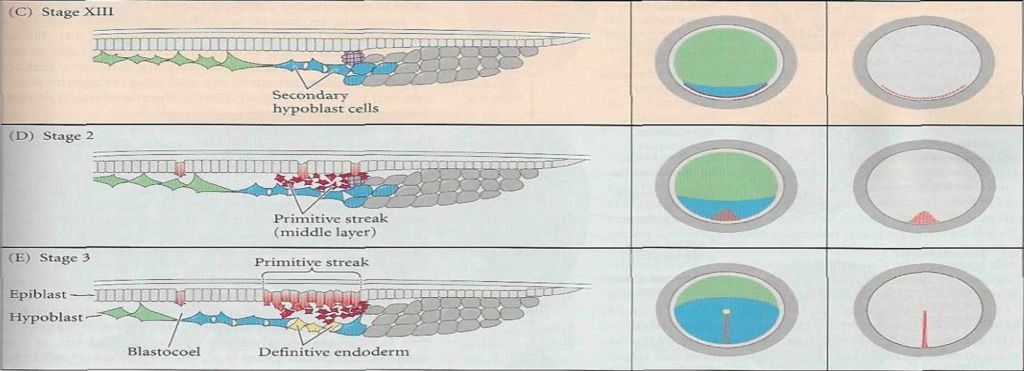

•Dye-marking experiments and time-lapse cine-micrography indicate that the primitive streak first arises from a local thickening of the epiblast at the posterior edge of the area pellucida, called Roller’s sickle, and the epiblast above it.

Formation of primitive streak

•The Streak is first visible as cells accumulate in the middle layer, followed by a thickening of the epiblast at the posterior marginal zone, just anterior to Roller’s sickle (Figure 8.3A).

•This thickening is initiated by an increase in the height (thickness) of the cells forming the center of the primitive streak.

•The presumptive streak cells around them become globular and motile, and they appear to digest away the extracellular matrix underlying them.

•This process allows these cells to undergo intercalation (mediolaterally) and convergent extension.

•Convergent extension is responsible for the progression of the streak— a doubling in streak length accomplishes by division halving of its width (Figure 8.3B).

•Those cells that initiate streak formation (i.e., the cells in the midline of the epiblast , overlying Roller’s sickle) appear to migrate anteriorly and may constitute a stable cell population that directs the movement of epiblast cells into the streak.

•As cells converge to form the primitive streak, a depression forms within the streak. This depression is called the primitive groove, and it serves as an opening through which migrating cells pass into the deep layers of the embryo.

•Thus , the primitive groove is homologous to the amphibian blastopore, and the primitive streak is homologous to the blastopore lips.

•At the anterior end of the primitive streak is a regional thickening of cells called Hensen’s node (also known as the primitive knot; Figure 8.3C).

•The center of Hensen’s node contains a funnel-shaped depression (sometimes called the primitive pit) through which cells can enter the embryo to form the notochord and prechordal plate.

•Hensen’s node is the functional equivalent of the dorsal lip of the amphibian blastopore (i.e., the organizer) and the fish embryonic shield.

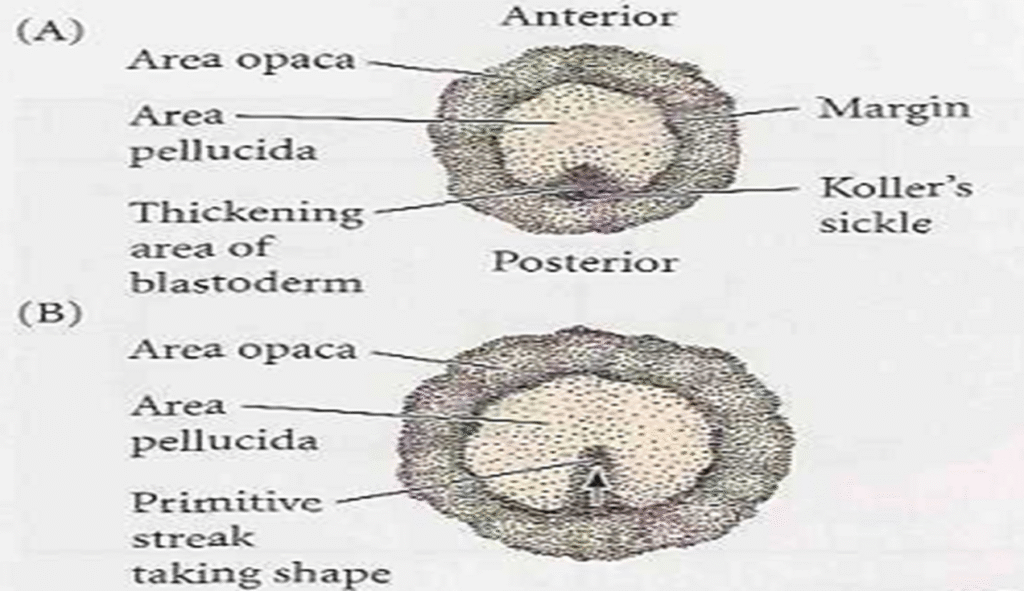

•The primitive streak defines the axes of the avian embryo. It extends from posterior to anterior; migrating cells enter through its dorsal side and move to its ventral side; and it separates the left portion of the embryo from the right.

•The axis of the streak is equivalent to the dorsal-ventral axis of amphibians.

•The anterior end of the streak (Hensen’s node) gives rise to the prechordal mesoderm, notochord, and medial part of the somites.

•Cells that ingress through the middle of the streak give rise to the lateral part of the somites and to the heart and kidneys.

•Cells in the posterior portion of the streak make the lateral plate and extraembryonic mesoderm.

•After the ingression of the mesoderm cells, epiblast cells remaining outside, but dose to, the streak will form medial (dorsal) structures such as the neural plate, while those epiblast cells farther from the streak will become epidermis.

•Elongation of primitive streak

•As cells enter the primitive streak, they undergo an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transformation, and the basal lamina beneath them breaks down.

•The streak elongates toward the future head region as more anterior cells migrate toward the center of the embryo.

•Cell division adds to the length produced by convergent extension, and some of the cells from the anterior portion of the epiblast contribute to the formation of Hensen’s node.

•At the same time, the secondary hypoblast (endoblast) cells continue to migrate anteriorly from the posterior margin of the blastoderm (see Figure 8.2E).

•The elongation of the primitive streak appears to be coextensive with the anterior migration of these secondary hypoblast cells, and the hypoblast directs the movement of the primitive streak.

•The streak eventually extends to 60-75% of the length of the area pellucida.

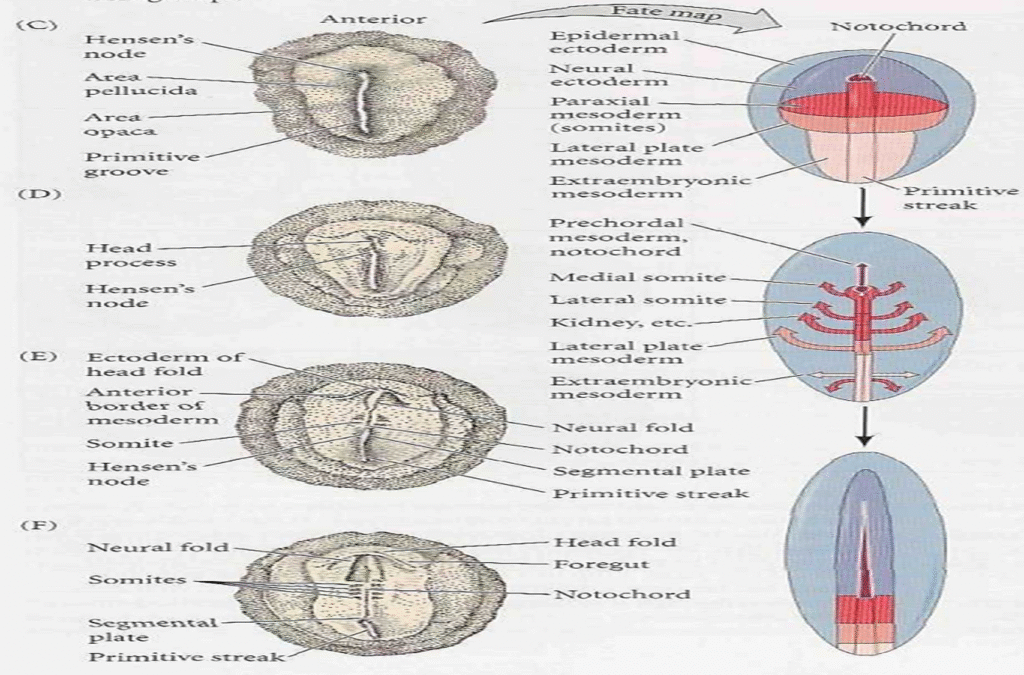

Formation of endoderm and mesoderm

•As soon as the primitive streak has formed, epiblast cells begin to migrate through it and into the blastocoel (Figure 8.4).

•The streak thus has a continually changing cell population.

•Cells migrating through the anterior end pass down into the blastocoel and migrate anteriorly, forming the endoderm, head mesoderm, and notochord; cells passing through the more posterior portions of the primitive streak give rise to the majority of mesodermal tissues.

•The first cells to migrate through Hensen’s node are those destined to become the pharyngeal endoderm of the foregut.

•Once deep within the embryo, these endodermal cells migrate anteriorly and eventually displace the hypoblast cells, causing the hypoblast cells to be confined to a region in the anterior portion of the area pellucida.

•This anterior region, the germinal crescent, does not form any embryonic structures, but it does contain the precursors of the germ cells, which later migrate through the blood vessels to the gonads.

•The next cells entering through Hensen’s node also move anteriorly, but they do not travel as far ventrally as the presumptive foregut endodermal cells.

•Rather, they remain between the endoderm and the epiblast to form the prechordal plate mesoderm.

•Thus, the head of the avian embryo forms anterior (rostral) to Hensen’s node.

••The next cells passing through Hensen’s node become the chordamesoderm.

•The chordamesoderm has two components: the head process and the notochord.

•The most anterior part, the head process, is formed by central mesoderm cells migrating anteriorly, behind the prechordal plate mesoderm and toward the rostral tip of the embryo (see Figures 8.3 and 8.4).

•The head process will underlie those cells that will form the forebrain and midbrain.

•As the primitive streak regresses (see below), the cells deposited by the regressing Hensen’s node will become the notochord.

•Migration of endodermal and mesodermal cells through the primitive streak.

•(A) Stereogram of a gastrulating chick embryo, showing the relationship of the primitive streak, the migrating cells, and the hypoblast and epiblast of the blastoderm.

•The lower layer becomes a mosaic of hypoblast and endodermal cells; the hypoblast cells eventually sort out to form a layer beneath the endoderm and contribute to the yolk sac.

Cells migrating through Hensen’s node travel anteriorly to form the prechordal plate and notochord; those migrating through the next anterior region of the streak travel laterally, but converge near the midline to make notochord and somites; those from the middle of the streak form intermediate mesoderm and lateral plate mesoderm (see the fate map in Figure 8.3). Farther posterior, the cells migrating through the primitive streak make the extraembryonic mesoderm (not shown).

•This scanning electron micrograph shows epiblast cells passing into the blastocoel and extending their apical ends to become bottle cells.