Introduction to stem cell

•A stem cell can be defined as a relatively undifferentiated cell that when it divides produces

•(1) one cell that retains its undifferentiated character; and

•(2) a second cell that can undergo one or more paths of differentiation.

•Thus, a stem cell has the potential to renew itself at each division (so that there is always a supply of stem cells) while also producing a daughter cell capable of responding to its environment by differentiating in a particular manner.

•In some organs, such as the gut, epidermis, and bone marrow, stem cells regularly divide to replace worn-out cells and repair damaged tissues. In other organs, such as the prostate and heart, stem cells divide only under special physiological conditions, usually in response to stress or the need to repair the organ.

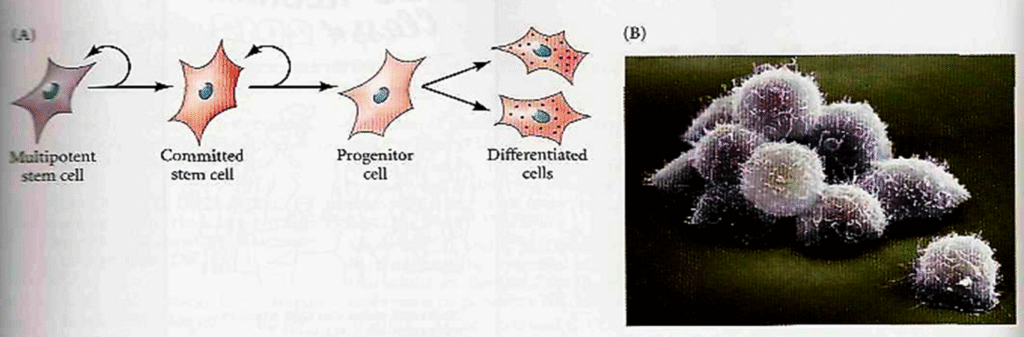

•The stem cell concept. (A) Stem cells have two distinct progeny at division: another stem cell and a more committed cell that can differentiate.

•(B) Hematopoietic stem cells isolated from human bone marrow form all the different blood cell types, as well as producing more hematopoietic stem cells.

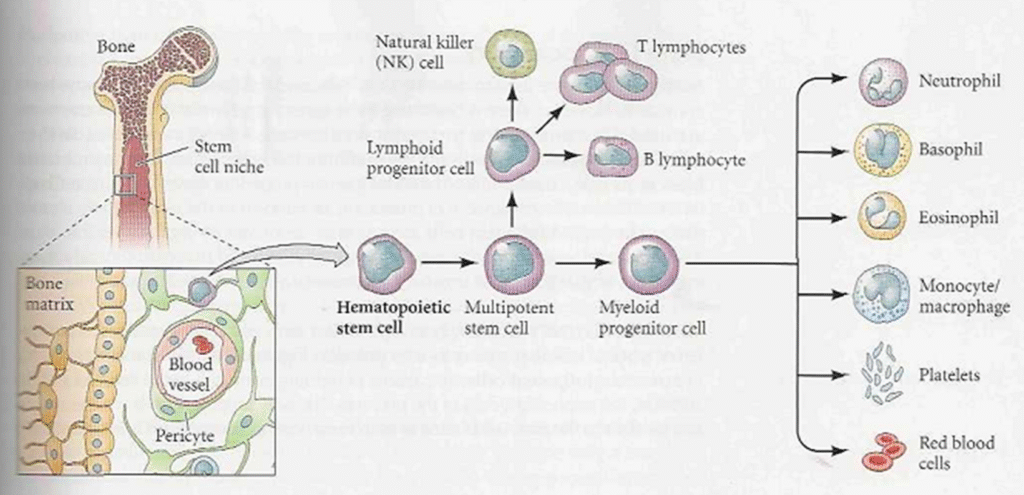

•Blood-forming (hematopoietic) stem cells and the bone marrow niche.

•The hematopoietic stem cell is located in the bone marrow and generates a second stem cell that is capable of becoming either a lymphocyte progenitor cell (which divides to form the cells of the immune system) or a myeloid stem cell (which forms the blood cell precursors).

•The type of lineage that the cells take is regulated by the niche, which involves contact between the stem cells and the matrices of bone cells, paracrine factors from stromal cells and the pericytes surrounding the blood vessels, and systemic hormones and neural signals.

•Mesenchymal stem cells also use the bone marrow as a niche.

Stem Cell Vocabulary

•Numerous terms are used to describe stem cells, and their usage has not always been consistent. However, there is beginning to be general agreement on how these terms are used.

•The names of the two major divisions of stem cells are based on their sources.

•Embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass of mammalian blastocysts or from fetal gamete progenitor (germ) cells. These cells are capable of producing all the cells of the embryo (i.e., a complete organism).

•Adult stem cells are found in the tissues of organs after the organ has matured. These stem cells, which are usually involved in replacing and repairing tissues of that particular organ, can form only a subset of cell types.

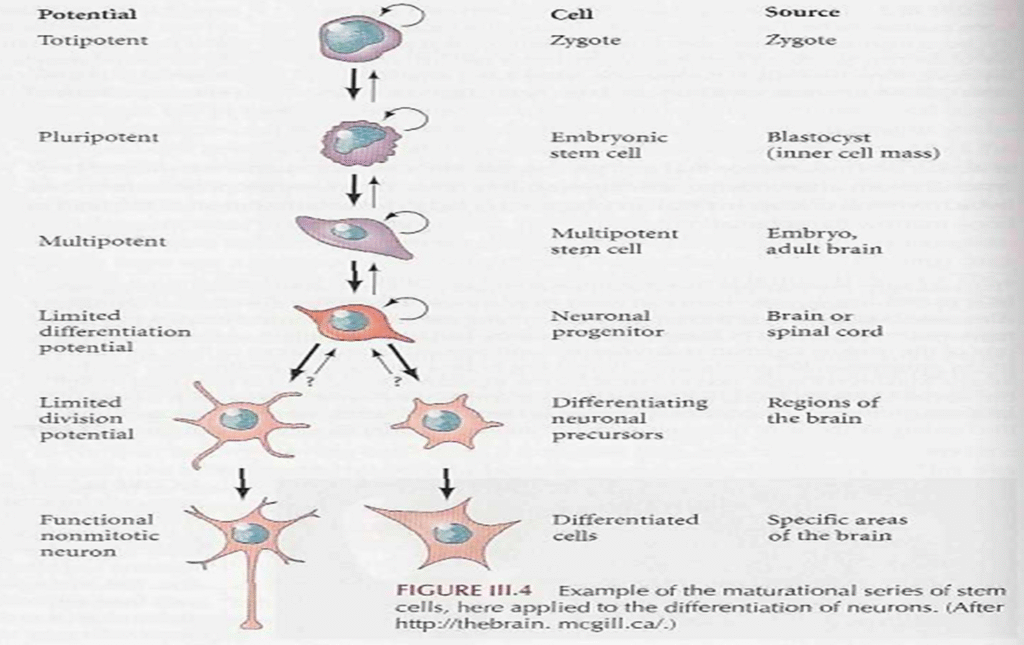

Stem cells potency

•STEM CELL POTENCY The ability of a particular stem cell to generate numerous different types of differentiated cells is its potency.

•In mammals, totipotent cells are capable of forming every cell in the embryo and, in addition, the trophoblast cells of the placenta. The only totipotent cells are the zygote and (probably) the first 4-8 blastomeres to form prior to compaction.

•Pluripotent stem cells have the ability to become all the cell types of the embryo except trophoblast. Usually these embryonic stem cells are derived from the inner cell mass of the mammalian blastocyst. However, germ cells and germ cell tumors (such as teratocarcinomas) can also form pluripotent stem cells.

•Multipotent stem cells are stem cells whose commitment is limited to a relatively small subset of all the possible cells of the body. These are usually adult stem cells.

•The hematopoietic stem cell, for instance, can form the granulocyte, platelet, and red blood cell lineages. Similarly, the mammary stem cell can form all the different cell types of the mammary gland.

•Some adult stem cells arc unipotent stem cells, which are found in particular tissues and are involved in regenerating a particular type of cell.

•Spermatogonia, for example, are stem cells that give rise only to sperm.

•Whereas pluripotent stem cells can produce cells of all three germ layers (as well as producing germ cells), the multipotent and unipotent stem cells are often grouped together as committed stem cells, since they have the potential to become relatively few cell types.

Progenitor cells

•PROGENITOR CELLS Although they are related to stem cells, progenitor cells are not capable of unlimited self-renewal; they have the capacity to divide only a few times before differentiating. They are sometimes called transit-amplifying cells, since they usually divide while migrating away from the stem cell niche.

•Both unipotent stem cells and progenitor cells have been called lineage restricted cells, but the stem cells have the capacity for self-renewal, while the progenitor cells do not.

•Progenitor cells are usually more differentiated than stem cells and have become committed to become a particular type of cell. In many instances, stem cell division generates progeny that become progenitor cells, as is seen in the formation of the blood cells, sperm cells, and the nervous system.

Adult Stem Cells

•Numerous adult organs contain committed stem cells that can give rise to a limited set of cell and tissue types.

•In addition to the well-known hematopoietic stem cells , developmental biologists have discovered epidermal stem cells, neural stem cells, hair stem cells, melanocyte stem cells, muscle stem cells, tooth stem cells, gut stem cells, and germline stem cells.

•Such cells are not as easy to use as pluripotent embryonic stem cells; they are difficult to isolate, since they often represent fewer than 1 out of every 1000 cells in an organ.

•In addition, they appear to have a relatively low rate of cell division and do not proliferate readily. However, neither of these facts precludes their usefulness.

Adult Stem Cell Niches

•Many tissues and organs contain stem cells that undergo continual renewal; these include the mammalian epidermis, hair follicles, intestinal villi, blood cells, and sperm cells, as well as Drosophila intestine, sperm, and egg cells.

•Such stem cells must maintain the long-term ability to divide, producing some daughter cells that are differentiated and other daughter cells that remain stem cells.

•The ability of a cell to become an adult stem cell is determined in large part by where it resides.

•The continuously proliferating stem cells are housed in compartments called stem cell niches. These are particular places in the embryo that allow the controlled proliferation of the stem cells within the niche and the controlled differentiation of the cell progeny that leave the niche.

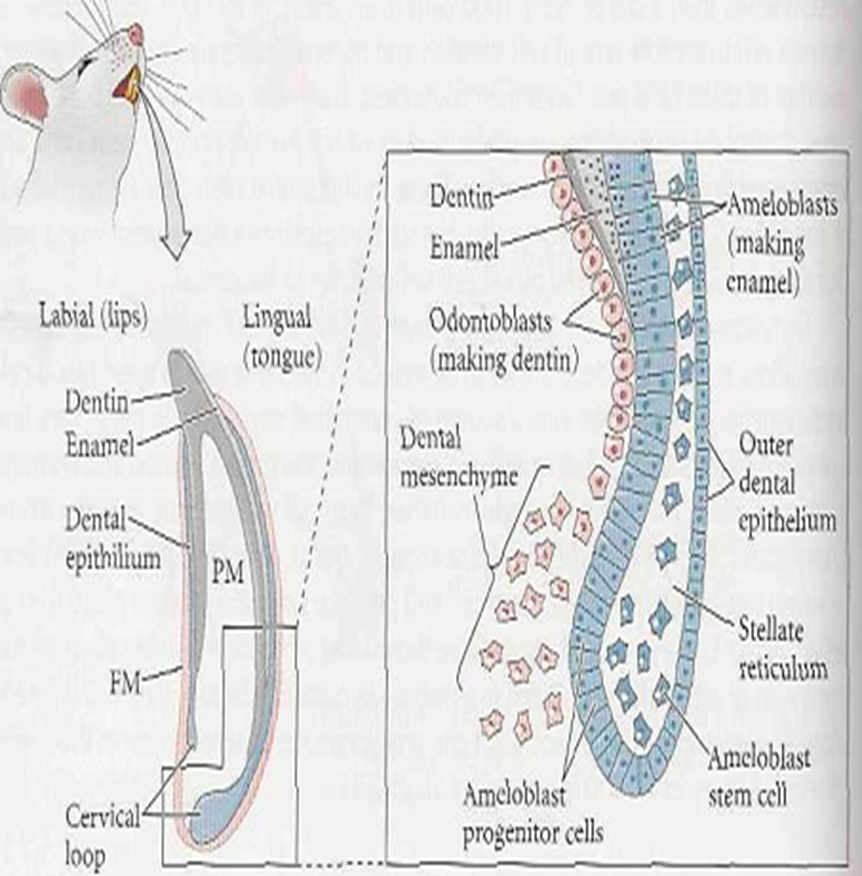

•The cervical loop of the mouse incisor is a stem cell niche for the enamel secreting ameloblast cells.

•These cells migrate from the base of the stellate reticulum into the enamel layer, allowing the teeth to keep growing.

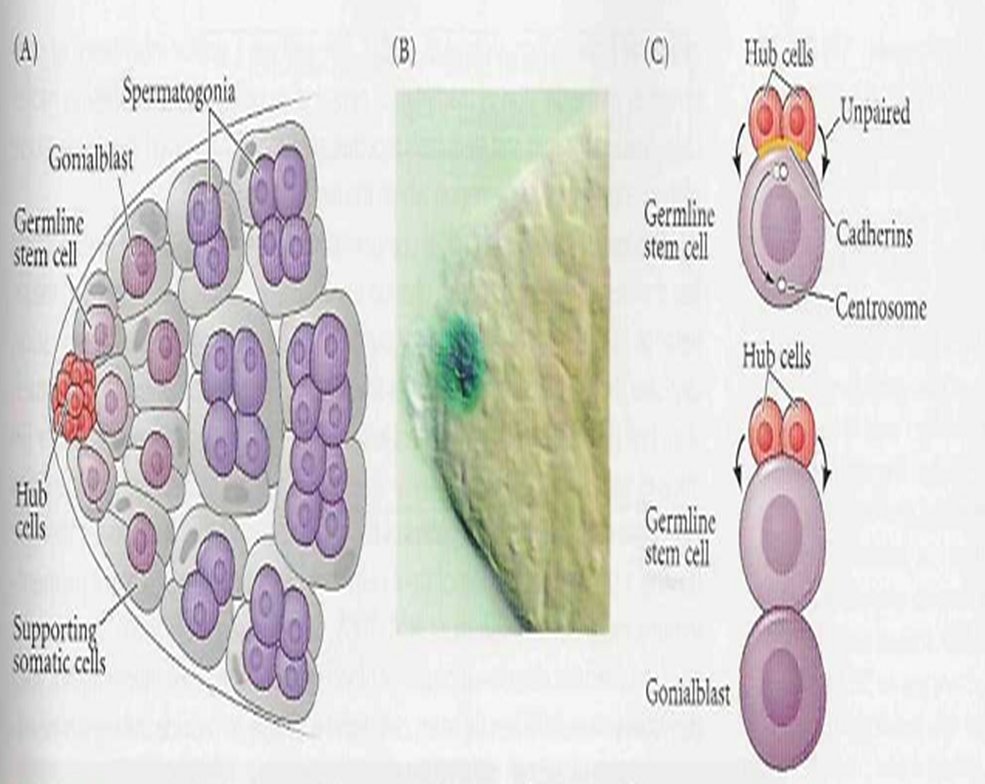

•Stem cell niche in Drosophila testes.

•(A) The apical hub consists of about 12 somatic cells, to which are attached 5-9 germ stem cells. The germ stem cells divide asymmetrically to form another germ stem cell (which remains attached to the somatic hub cells) and a gonialblast that will divide to form the sperm precursors (the spermatogonia and the spermatocyte cysts where meiosis is initiated).

•(B) Reporter ß-galacto$idase inserted into the gene for Unpaired reveals that this protein is transcribed in the somatic hub cells.

•(C) Cell division pattern of the germline stem cells, wherein one of the centrosomes remains in the cortical cytoplasm near the site of hub cell adhesion, while the other centrosome migrates to the opposite pole of the germline stem cell. This results in one cell remaining attached to the hub and the other cell detaching from it and differentiating.